Learning diagnostic correlations: ECE to Interferometer reconstruction

Before investigating a multimodal ML-based model to generate synthetic SRTS using other diagnostics, it is crucial to first verify the existence, strength, and robustness of their underlying correlations. We therefore begin by demonstrating a fundamental capability of ML: leveraging one diagnostic’s measurements to reconstruct another’s. Specifically, we use ECE spectrograms, spatially resolved measurements with about 40 channels from edge to core, to reconstruct the line-integrated density fluctuation signals of the Interferometer. Because certain plasma instabilities and modes, such as Alfvén Eigenmode (AE), manifest in both temperature and density measurements, it is reasonable to expect that correlations exist between ECE and Interferometer measurements during such events. Here, we show that a convolutional neural network (CNN) can learn these correlations and reconstruct Interferometer spectrograms from ECE spectrograms, as illustrated in Fig. 2.

a The configuration of four Interferometer chords (R0, V1-3) and 40 ECE probes at DIII-D. b A tensor of (40 × time × frequency) is supplied to CNN. c The configuration of CNN. d Visual comparison of measured and reconstructed spectrograms for DIII-D discharge 170669. e Comparison of the Alfven Eigenmode detector output23 supplied with the measured and reconstructed spectrograms.

Figure 2a shows the measurement positions and paths of ECE and Interferometer, as well as example spectrograms obtained from their raw signals (Fig. 2b, d). We designed and trained a CNN that takes 40 ECE spectrograms as input and reconstructs 4 target Interferometer spectrograms. The reconstructed synthetic Interferometer spectrograms visually confirm the plausible reconstruction of features such as frequency chirping and harmonics, especially during the AE events22, as seen in Fig. 2d.

To evaluate how well the underlying physical content is preserved in the reconstructed spectrograms, we employ both quantitative and physics-based assessments. First, achieving an \({{\mathscr{L}}}1\) loss of 1.2 × 10−3 on the validation set determines how closely the CNN reconstructions match the Interferometer’s amplitude and time-frequency distribution (see the section “Methods” subsection “Spectrogram model development” for more details). Second, to verify that the essential physics is captured, we apply a previously published AE detection algorithm23, originally designed for interferometer data, to both the original and reconstructed spectrograms. The resulting average F1 score of 0.82 on the validation set after applying a threshold of 0.15, as suggested in ref. 23, indicates that the model largely reproduces the AE modes, reflecting a high degree of physics fidelity in the reconstructed signals. These findings confirm that neural networks can extract and retain the intrinsic correlations among diagnostic data, even when only one diagnostic serves as input.

Having established the efficacy of this unimodal-to-unimodal reconstruction using spectrogram data, we next extend our approach to raw time-series inputs and expand to multimodal cases. In the subsequent sections, we focus on generating TS signals from a diverse set of diagnostics, illustrating the broader potential of our method for super-resolution diagnostic reconstruction.

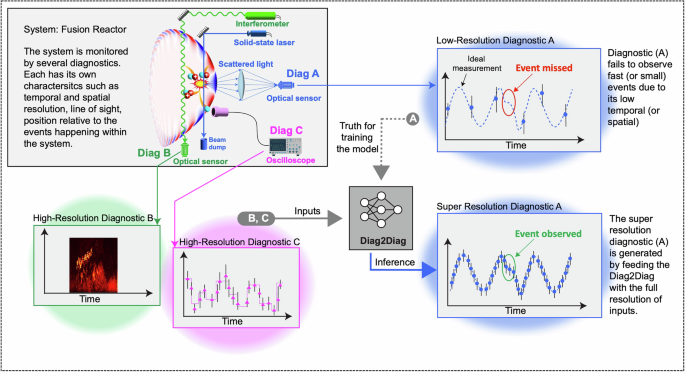

Generating super-resolution Thomson Scattering from complementary diagnostics

In this section, we switch from spectrograms to time-series signals and show that the amplitude of a diagnostic can be reconstructed from other diagnostics, while preserving intrinsic physics. More importantly, we will show that if the input diagnostics are of much higher temporal resolution compared to the target one, such a model can be used to increase the time resolution of the target signals in a much more intelligent way compared to the conventional unimodal interpolations. As a use case, we target TS, one of the most important diagnostics that measures the electron density and electron temperature profile of plasma. However, as mentioned earlier, its low temporal resolution is a bottleneck in studying the plasma evolution in the rapidly changing events such as ELM.

Figure 3 demonstrates a diagram of the data processing pipeline during training and inference of Diag2Diag. We consider a suite of input diagnostics available at DIII-D, including Interferometer, ECE, Magnetic probes (Magnetics), Charge Exchange Recombination (CER), and MSE with typical sampling rates of 1.66 MHz, 500 kHz, 2 MHz, 200 Hz, and 4 kHz, respectively. Since our aim is not only to enhance TS but also to reconstruct it from other diagnostics, we do not use the available measurement of TS as input to Diag2Diag. To obtain a dataset that can be used to train and validate the model with the available TS measurements, all the included diagnostics are aligned with the TS sampling time steps by matching their most recent measured sample.

a During the training, the inputs are aligned and resampled with respect to TS timing, to have a ground truth for training and validation of the model. b During the inference, the inputs are resampled to 1 MHz, which will be the resolution of synthetic SRTS. Since there is no ground truth for data-driven validation, we validate the SRTS by studying its behavior during fast physics phenomena, which are challenging to analyze with measured TS due to its low temporal resolution.

Since the sampling steps of TS, which is also used to align the inputs for training the model, are not always uniform in time, we opted for a feed-forward neural network instead of recurrent neural networks, which are commonly used in time-series analysis. However, we included the first and second derivatives of the high-resolution input diagnostics, ECE and Interferometer, to include the temporal evolution information. During the inference, the input diagnostics are aligned to a fixed sampling rate of 1 MHz to generate synthetic SRTS. The neural network consists of three dense layers with 512, 256, and 128 nodes per hidden layer. More details about the dataset preparation, model optimization, and uncertainty quantification are provided in sections “Methods” subsection “Time-series model development” and “Discussion” “Assessing model and measurement uncertainty”.

Figure 4 shows, in blue, synthetic SRTS signals generated through the inference of Diag2Diag for the DIII-D discharge 153761, and the original TS measurements are also shown with black dots. For this discharge, TS was fired in the highest possible temporal resolution, so-called “burst mode” (see section “Methods” subsection “Diagnostic constraints in ELM measurements” for more details). We can observe that the synthetic signals closely follow the original measurements, achieving an R2 score of 0.92 in reconstructing the available TS measurement on the validation set. Diag2Diag’s ability to reconstruct TS from other diagnostics ensures that crucial information is not lost, even in the absence of direct measurements. Furthermore, while the original TS measurement sometimes fails to capture ELM events, the synthetic SRTS accurately captures the events missed by TS.

a Comparison of the electron density by the measured TS and SRTS, for discharge 15376115 near the edge (Z = 0.71 m). The spectral emission, Dα, is plotted as an indicator of ELMs. b, c An example of an ELM event captured by both diagnostics, and examples only captured by SRTS are highlighted in green and red, respectively.

Here, we note that our objective is not to replicate the entire physics of Magnetohydrodynamics (MHD) turbulence in plasma24 from first principles, but rather to learn empirically grounded correlations among multiple diagnostics. Our aim is to show that even a modestly sized neural network can reliably capture significant nonlinear relationships, for instance, shared fluctuations or mode signatures, by training on experimental data where these diagnostic measurements overlap in time and space. Crucially, the model does not need a complete, fundamental understanding of turbulence; instead, it identifies and exploits observed patterns that consistently appear across diagnostics, as confirmed by its alignment with known plasma behaviors and successful performance on held-out data. Thus, while the network’s architecture may be relatively straightforward, it remains effective in generating physically meaningful reconstructions in a manner that is both computationally efficient and broadly adaptable, complementing (rather than replacing) fundamental physics-based models of MHD turbulence.

Benchmarking super-resolution TS against ELM cycle dynamics at DIII-D

When ELM instability occurs, a large amount of plasma quickly escapes from the boundary within milliseconds, and then the plasma gradually recovers. TS diagnostics can observe the density and temperature structure at this edge region, but are limited in capturing dynamics occurring over milliseconds. Recent research overcame these resolution limits by statistical analysis and aggregating the measurements from multiple repeated cycles of the fast activity under almost identical conditions to observe a complete evolution25. In that work, over 20 highly reproduced cycles of ELM crash and recovery were aggregated from DIII-D discharge 174823 to assume a ground truth of a complete evolution of an ELM cycle.

The aggregated density and temperature evolution measured by TS in three locations of plasma near the edge are shown in Fig. 5a, b with transparent crosses, while measurements from a single cycle are shown with circles and different colors for different measurement locations. In a more typical tokamak discharge, the plasma state continually changes, and ELMs occur more irregularly, as shown in Fig. 4. In such cases, it is not possible to reconstruct a single ELM cycle by aggregating multiple cycles, and our SRTS method will be highly beneficial.

a, b Aggregating the measured TS density and temperature in three locations of plasma near the edge for several ELM cycles of the DIII-D discharge 174823. The circle highlights the measures TS for one selected ELM cycle, and the solid lines present the SRTS, which agreeably match the measured TS. t = 0 represents the time when ELM is identified by Dα. c, d The evolution of SRTS between two consecutive measured TS near one ELM cycle across the plasma location.

We used the Diag2Diag model to generate synthetic SRTS, shown with solid lines in Fig. 5a, b. The SRTS signal from a single cycle around time 3795 ms not only follows the trend of the aggregated multiple TS measurements but also well overlays the TS measurements within that cycle. Fig. 5c, d shows the detailed evolution of plasma density and temperature across the plasma location captured by SRTS in the same ELM cycle at 3795 ms, which is missed by TS between its two consecutive measurements at 3791 ms and 3800 ms.

Science discovery: unveiling diagnostic evidence of the RMP mechanism on the plasma boundary

In what follows, we investigate whether the synthetic super-resolution diagnostics can help to verify the hypotheses on the mechanism of plasma response to external field perturbations in fusion plasma physics that have been proposed theoretically or by simulations but have never been visualized with experimental data due to the lack of diagnostic resolution.

One promising strategy to control ELMs is employing RMPs26,27,28,29,30,31 generated by external 3D field coils depicted in Fig. 6a. These fields effectively reduce the temperature and density at the confinement pedestal, stabilizing the energy bursts in the edge region. Consequently, ITER will rely on RMPs to maintain a burst-free burning plasma in a tokamak, making it essential for the fusion community to understand and predict its physics mechanism32. However, this issue has remained a challenge for decades.

Structure of 3D coils and islands by perturbed field (a), along with the evidence in the simulation (b–d) and SRTS diagnostic (e–g) for RMP-induced island mechanism on the plasma boundary in DIII-D discharge 157545.

The leading theory33,34,35,36 for explaining the reduced pedestal by RMPs is the formation of magnetic islands by an external 3D field. The magnetic island is a ubiquitous feature in an electromagnetic system with plasmas37 formed by field reconnection38,39. This structure allows rapid heat (or temperature) and particle (or density) transport between adjacent magnetic field lines, strongly reducing the gradient of local heat and particle distribution, or, in other words, profile flattening40. The existing theories explain that RMP forms static magnetic islands at the pedestal top and foot region, therefore reducing the pedestal by local profile flattening. As illustrated in Fig. 6a, the theory predicts that RMPs can create magnetic islands near the plasma boundary where the pedestal sits. This model has been successful in quantitatively explaining and predicting the RMP-induced pedestal degradation in real experiments35,41, reinforcing magnetic islands as a promising mechanism for RMP-induced pedestal degradation. Nevertheless, measuring evidence of island or local profile flattening still remains a challenge. Extensive experimental efforts have been conducted for this reason and were able to capture the local flattening electron temperature profile42 near the pedestal top, strongly supporting this theory. However, simultaneously measuring electron temperature and density both at the pedestal top and foot was not possible. In a previous study, rough evidence was observed in TS36, but it was insufficient to derive a concrete conclusion, mainly due to a large uncertainty of measurement originating from the narrow structure (expected from theory, see Fig. 6a) and oscillatory nature of the plasma boundary. To address the diagnostic uncertainties caused by such system oscillation, one method is to increase the time sampling rate and use time averaging. However, in conventional TS, increasing the time resolution results in a trade-off with measured accuracy, eventually leading to observational limitations.

Interestingly, the SRTS has once again illuminated the profile evolution by RMP application, providing the novel evidence of “simultaneous” flattening of temperature and density profile at both the top and the foot of the pedestal, strongly supporting the theoretical prediction of the magnetic islands effect. This is possible by capturing the statically reliable time trace of the profile with the Chebyshev time filter, leveraging the enhanced temporal resolution by SRTS.

Figure 6b–g illustrates the recovery of temperature and density pedestals within 10 ms after deactivating RMP, as captured through numerical modeling (Fig. 6b–d) and SRTS (Fig. 6e–g). The simulations reveal that the recovery of temperature and density pedestals begins at the top and foot, coinciding with the disappearance of islands. As depicted in Fig. 6d, g, the profile gradient recovers at these island locations, enhancing the overall profile. For instance, the measured temperature pedestal shows recovery at both the top and the foot through an increasing gradient, displaying qualitative alignment with the simulation results. However, some discrepancies are noted, particularly in the density evolution at the pedestal foot in the SRTS, even though its gradient remains consistent with the modeling. These quantitative differences may stem from the TS’s limited spatial resolution at the boundary and the modeling assumptions, such as fixed boundary conditions43. Nevertheless, the gradient evolution directly indicates a change in transport due to the RMP-induced islands during this perturbative profile evolution, highlighting that the SRTS successfully reveals the experimental island effect. This provides the new diagnostic evidence of profile flattening at magnetic islands, a key mechanism of RMP-induced pedestal degradation.

The strength of the SRTS in unveiling profile flattening during ELM suppression can be further highlighted with additional cases. Fig. 7 shows the time traces of plasma for DIII-D discharge 136219 when the edge safety factor (q95), the magnetic pitch angle at the plasma edge, gradually decreases. Here, all other plasma operation parameters, including the RMP field, remain the same. From Dα emission looking perturbation of plasma edge (see Fig. 7a), the bursty spikes disappear during q95 = 3.5–3.6, corresponding to the ELM-suppressed phase followed by the transient ELM-free phase. This shows the strong dependence of ELM suppression on q95. The modeling work based on the island physics42 was able to explain this behavior through the sensitivity of island width at the pedestal top, where its width abruptly increases at certain q95 values due to nonlinear RMP response44. When the island becomes bigger, it leads to local flattening of electron pressure (Pe, product of temperature and density), resulting in ELM suppression. This explanation has successfully predicted this q95 dependency in multiple devices44. However, its experimental validation remains challenging as plasma becomes perturbative while q95 changes, making the pedestal diagnostic oscillatory. Such diagnostic oscillation can be overcome by time filtering, but the temporal resolution of TS was limited for resolving pedestal evolution with q95 with filtering processing.

a Time evolution of edge safety factor (q95) and Dα emission at plasma edge for DIII-D discharge 136219. b Contour of electron pressure versus normalized plasma radius and time. The numerically derived width of the magnetic island at the pedestal top is illustrated as green contours. c Comparison of TS (blue), SRTS (red), and filtered SRTS (orange solid line).

The SRTS has once again derived the profile evolution by q95 change, providing novel evidence of profile flattening of the pressure profile at the top of the pedestal, leveraging the enhanced temporal resolution by SRTS. Fig. 7b illustrates the strong flattening of the pressure profile during the ELM-suppressed phase, coinciding with the location and width of the magnetic island from numerical modeling. Fig. 7c shows the electron pedestal height measured in both TS and SRTS of the nearest channel to the pedestal top, where the filtered SRTS (orange solid line) follows TS while overcoming diagnostic oscillations. This successfully extracts a prominent impact (profile flattening) on the pedestal caused by island widening from evolving plasma, leveraging the enhanced temporal resolution. This successful application of SRTS underscores its potential to reveal new physics beyond the limitations of conventional diagnostic techniques.