Physical model

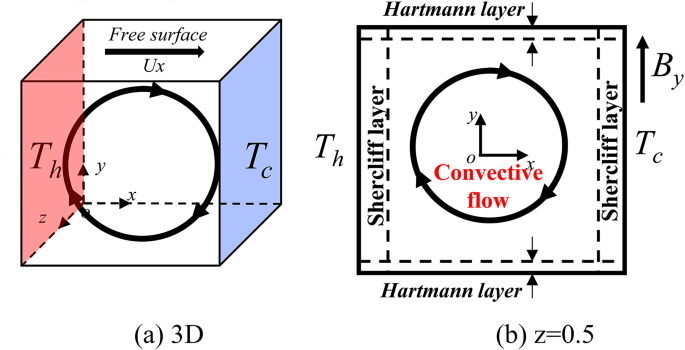

To model Marangoni convection within a three-dimensional, cubic cavity under the influence of a magnetic field, a physical model was established, as illustrated in Fig. 1. The cubic cavity is configured with each side having a length of one unit. The left wall of this cavity maintains a constant high temperature (Th = 1), while the right wall is kept at a constant lower temperature (Tc = 0). The remaining four walls of the cavity are insulated, exhibiting adiabatic properties. This configuration results in a temperature gradient between the walls at constant temperature. The top surface of the cavity is a free surface, with the magnetic field aligned along the x, y, and z directions. To streamline the simulation, the following assumptions were adopted: (1) The fluid within the cavity is an incompressible Newtonian fluid with constant physical parameters, except for the surface tension, which varies. (2) Deformations of the free surface are disregarded in the model. (3) The effects of natural convection are excluded in this configuration. (4) Thermal capillarity is accounted for on the free surface, representing the Marangoni effect. The surface tension is assumed to be a linear function of temperature, \({\sigma }_{s}={\sigma }_{s0}-\gamma ({T}-{{T}}_{0})\), where \(\gamma =-\partial {\sigma }_{s}/\partial {T}\) represents the surface tension coefficient.

(a) Schematic diagram of the computational model (a cubic cavity with a side length of one unit, filled with liquid metal. Magnetic fields are applied along the x, y, or z directions. (b) Schematic diagram of the Hartmann layer and Shercliff layer on the z = 0.5 plane when the magnetic field is oriented in the y-direction.

Governing equations

In this study, all magnetic Reynolds numbers are much less than 1,

$$Re_{m} = U_{0} l\sigma_{e} \mu_{m} \ll 1$$

(1)

Here \({U}_{0}\) and \(l\) represent the characteristic velocity and length, respectively, \({\sigma }_{e}\) denotes the electrical conductivity of the fluid, and \({\mu }_{m}\) signifies the magnetic permeability of the liquid metal. In cases where the magnetic Reynolds number is low, the magnetic field generated by the fluid’s motion is deemed negligible relative to the externally applied magnetic field. Owing to the low-velocity nature of such systems, Joule dissipation—the conversion of electrical energy into heat energy due to resistance—can be largely disregarded in comparison to the prevailing heat flux. The governing equations, incorporating the Lorentz force as a body force term, describe the flow and heat transfer of the incompressible liquid metal:

$$\rho \left( {\frac{{\partial {\varvec{u}}}}{\partial t} + {\varvec{u}} \cdot \nabla {\varvec{u}}} \right) = – \nabla p + \mu \nabla^{2} {\varvec{u}} + {\varvec{J}} \times {\mathbf{B}}$$

(2)

$$\nabla \cdot \user2{u = }0$$

(3)

$$\frac{\partial T}{{\partial t}} + {\varvec{u}} \cdot \nabla T = \alpha \nabla^{2} T$$

(4)

$${\varvec{J}} = \sigma_{e} ( – \nabla \varphi + {\varvec{u}} \times {\mathbf{\rm B}})$$

(5)

$$\nabla \cdot {\varvec{J}} = 0$$

(6)

Here \(T\) represents the temperature, \(\alpha\) represents the thermal diffusion coefficient, \(\rho\) denotes the fluid density, \(\mu\) indicates the dynamic viscosity, and \({\varvec{u}}\) and \(p\) are the velocity vector and pressure, respectively. \({\varvec{J}}\) and \({\varvec{B}}\) symbolize the induced current and magnetic field, respectively. The cross product \({\varvec{J}}\times {\varvec{B}}\) signifies the Lorentz force. Equations (5) and (6) embody Ohm’s law and the current conservation principle, where \({\sigma }_{e}\) denotes the electrical conductivity and \(\varphi\) signifies the induced potential. The surface tension at the free surface varies linearly with temperature:

$${\sigma }_{s}={\sigma }_{s0}-\gamma ({T}-{{T}}_{0})$$

(7)

Here \({\sigma }_{s0}\) represents the surface tension of the liquid metal at its melting point, \({T}_{0}\) denotes the melting point temperature, and γ signifies the surface tension coefficient,

$$\gamma =-\partial {\sigma }_{s}/\partial {T}$$

(8)

Nondimensionalization yields three key dimensionless numbers. Re represents the ratio of the driving force induced by the surface tension gradient to the viscous force, reflecting the relative importance of surface tension-driven convection compared to viscous resistance and thermal diffusion. It is defined as:

$$Re=\gamma ({T}-{{T}}_{0})l/\mu \alpha$$

(9)

The Prandtl number (Pr), a fluid property, governs the ratio of viscous diffusivity to its thermal diffusivity. Significantly affecting the boundary layer thicknesses in low-Pr liquid metals, and is given by:

$$Pr=\frac{\nu }{\alpha }$$

(10)

In the presence of a strong magnetic field, the liquid metal flow is subjected to the electromagnetic force, and the Hartmann number (Ha) characterizes the relative magnitude of the electromagnetic force to the viscous force, and is expressed as:

$$Ha=l{B}_{0}\sqrt{{\sigma }_{e}/\mu }$$

(11)

In this study, the Prandtl number Pr was fixed at 0.025, and the analysis of flow and heat transfer was predominantly performed by varying Re and Ha. In the analysis of convective heat transfer, Nu functions as a crucial dimensionless parameter for quantifying heat transfer efficiency and is typically defined as follows:

$$N{u}_{local}\left(x,y,z\right)=-\frac{\partial T}{\partial x}$$

(12)

The average Nu number in the x-plane can be defined as:

$$Nu\left(x\right)=\iint \left(-\frac{\partial T}{\partial x}\right)dydz$$

(13)

Boundary conditions

The boundary conditions applied in the simulation are as follows:

The walls are perfectly electrically insulated as follows:

$$\frac{\partial \varphi }{\partial n}=0 at x ,y ,z=0, 1$$

(14)

Regarding the velocity,

$$\mu \frac{\partial u}{{\partial y}} = \gamma \frac{{\partial {T}}}{\partial x},\mu \frac{\partial w}{{\partial y}} = \gamma \frac{{\partial {T}}}{\partial z} at y = 1$$

(15)

The remaining walls are subjected to no-slip conditions.

Concerning the temperature,

$$\frac{\partial T}{\partial n}=0 at y , z=0, 1$$

(16)

Numerical method and validation

This study is based on magnetohydrodynamics (MHD) theory and employs the direct numerical simulation (DNS) method, utilizing the UCAS software platform17,30 to numerically solve the governing equations via the finite volume method. The coupling of pressure and velocity is achieved using a second-order accurate pressure correction algorithm. A consistent and conservative numerical scheme31 is adopted to solve the potential Poisson equation for determining the potential φ. Convective terms are discretized using central differencing, while pressure gradient, viscous, and body force terms are approximated with second-order accuracy. Time advancement is performed using a second-order implicit Euler method. The velocity–pressure system is solved using a preconditioned biconjugate gradient (PBiCG) solver with diagonal incomplete LU (DILU) preconditioning (suitable for asymmetric matrices), while the pressure and potential equations are solved using a preconditioned conjugate gradient (PCG) solver with diagonal incomplete Cholesky (DIC) preconditioning (suitable for symmetric matrices).

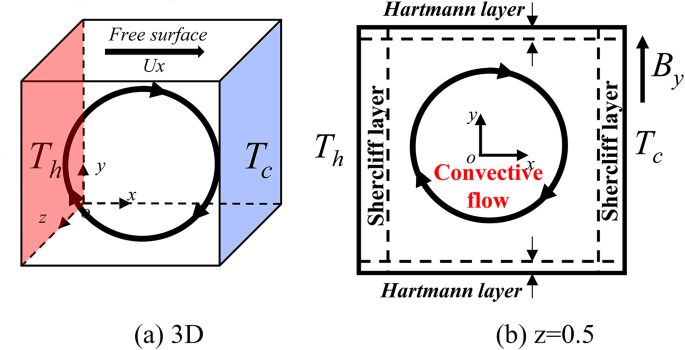

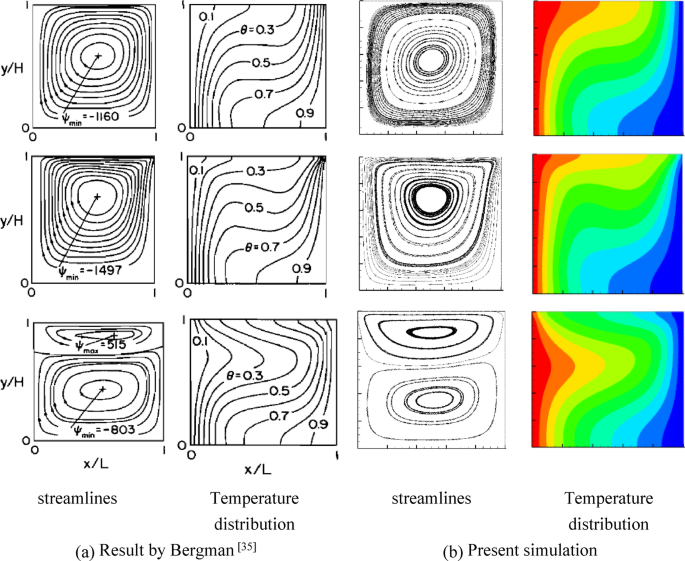

To verify the accuracy of the computational program for Marangoni convection under the influence of a magnetic field, the numerical model was validated against established benchmarks for Marangoni convection. As shown in Fig. 2, streamlines and temperature distributions in a cubic cavity with differentially heated sidewalls align closely with those of Bergman32, thereby affirming accuracy of the model.

Comparisons of streamlines and temperature distributions between the present simulation and the results of Bergman.

To further validate the accuracy of the numerical model, this study conducted a quantitative comparison. For the Marangoni convection case (Re = 10,000, Pr = 1) reported by Xu et al.33, we compared the free surface velocity, the average Nusselt number at the hot and cold walls, the vortex center coordinates, and the vorticity. The relative errors were all less than 2.3% (see Table 1).

Computational grids and grid refinement test

To obtain accurate numerical simulation results for magnetohydrodynamic (MHD) Marangoni convection, it is essential to adequately resolve the Hartmann layer (a boundary layer formed at walls perpendicular to the magnetic field) and the Shercliff layer (a boundary layer formed at walls parallel to the magnetic field). As shown in high-Ha duct flow simulations34,35,36, such resolution is sufficient to accurately capture the effects of boundary layers on complex turbulent and convection-dominated flows. Considering that the nondimensional thicknesses of these layers scale as Ha-1 and Ha-1/2, respectively, resolving them in high-Ha flows poses significant challenges. To ensure computational accuracy, the mesh near the walls is refined, with grid points distributed according to a geometric progression with a common ratio of 1.1. The final grid adopted in this study includes 6 grid points within each Hartmann layer and 12 grid points within each Shercliff layer. In this manner, appropriate grid parameters capable of yielding accurate results were determined. Additionally, a grid sensitivity study was conducted using three different meshes, G1(80 × 80 × 80), G2(100 × 100 × 100), and G3(120 × 120 × 120), to verify grid independence and simulate the flow at Re = 100,000 and Ha = 0. Table 2 presents the Nux=0 values obtained from different meshes. To balance sufficient accuracy for solving the current flow while optimizing computational cost, mesh G2 was selected for the simulation.