In this experiment, rows of components were cut using various cutting parameters, followed by photographing and observing the resulting damage. The observed damage primarily includes cutting marks and the condition of the cross-section on both the fuel rod components and the stainless steel wire wraps. Table 3 details the specific parameters used for each experiment, such as cutting speed, focal position, power, type of assist gas, and gas pressure.

Cutting results under different gaseous medium (a) air (b) nitrogen.

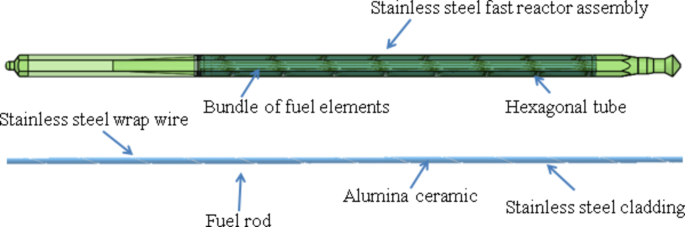

Figure 5 shows the cross-sectional views of laser cuts using two different assist gases: (a) air and (b) nitrogen. From a scientific perspective, the choice of assist gas plays a critical role in the quality and precision of laser cutting.

In the case of air as an assist gas (a), the cutting surface appears rougher with more evident thermal damage and oxidation. This can be attributed to the presence of oxygen in air, which promotes combustion and leads to the formation of oxides on the cut surface, degrading the overall cut quality. Oxidation not only increases surface roughness but also potentially weakens the mechanical properties of the cut edges. In contrast, the nitrogen-assisted cut (b) exhibits a cleaner surface with less thermal damage. Nitrogen, being an inert gas, prevents oxidation and results in a smoother cut edge. This is particularly advantageous for aluminum oxide ceramic, where oxidation-free cuts are often desired for both aesthetic and structural reasons. The reduced presence of oxides and smoother edges in the nitrogen cut make it a more suitable option for high-precision applications requiring minimal post-processing.

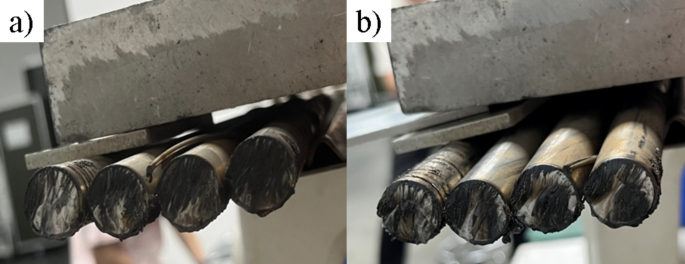

Kerf width under different cutting parameters (a) Kerf width at different cutting speeds. (b) Kerf width at different focal positions. (c) Kerf width at different powers. (d) Kerf width at different air pressures.

Figure 6 presents the kerf width variations under different cutting parameters—cutting speed, focal position, laser power, and gas pressure. Each parameter has a significant impact on the kerf width, and the observed trends provide insights into the cutting process.

At lower speeds (e.g., 0.3 m/min), the laser has a longer interaction time with the material, resulting in greater heat input and wider kerfs due to excessive melting. As the cutting speed increases (e.g., 1 m/min), the interaction time decreases, reducing heat input and material melting, leading to narrower kerfs. However, excessively high speeds may cause incomplete cuts as the laser energy may not sufficiently penetrate the material. A balance is achieved at moderate speeds, where sufficient energy is delivered without causing excessive material removal. The focal position affects how the laser energy is distributed within the material. A deeper focal position (e.g., − 25 mm) focuses energy more precisely within the material, resulting in narrower kerfs. However, if the focal point is too deep, it may lead to uneven cuts due to insufficient energy near the surface. Shallower focal positions (e.g., − 15 mm) spread the laser energy more across the surface, causing more material to melt and increasing the kerf width. The optimal range, as shown in the results, is between − 20 mm and − 25 mm, where the balance between depth and surface energy leads to the cleanest cuts. Higher laser power (e.g., 12,000 W) delivers more energy, which increases the kerf width by causing excessive material melting. Lower power (e.g., 7200 W) results in narrower kerfs, as less energy is absorbed by the material, preventing unnecessary melting beyond the cut line. However, if the power is too low, it may not fully penetrate the material, leading to incomplete cuts. The optimal power range (7200 W to 9600 W) achieves a balance by providing enough energy for clean cuts without excessive melting. Gas pressure aids in removing molten material and preventing oxidation. Higher pressures (e.g., 18 MPa with air) can cause turbulence in the cutting zone, leading to wider kerfs due to irregular material ejection. Lower pressures (e.g., 10 MPa) produce more controlled cuts with narrower kerfs. Nitrogen as the assist gas produces less oxidation and narrower kerfs compared to air, and is less sensitive to pressure variations. This makes nitrogen more effective for maintaining precise cuts.

The kerf width is influenced by the balance of laser parameters. Higher cutting speeds, deeper focal positions, and moderate power settings result in narrower kerfs and better precision, while lower speeds, shallow focal positions, and higher power increase the kerf width due to excessive material melting. Gas pressure and type, particularly the use of nitrogen, also contribute to more controlled cuts and narrower kerfs. These observations highlight the importance of optimizing these parameters for efficient and precise laser cutting.

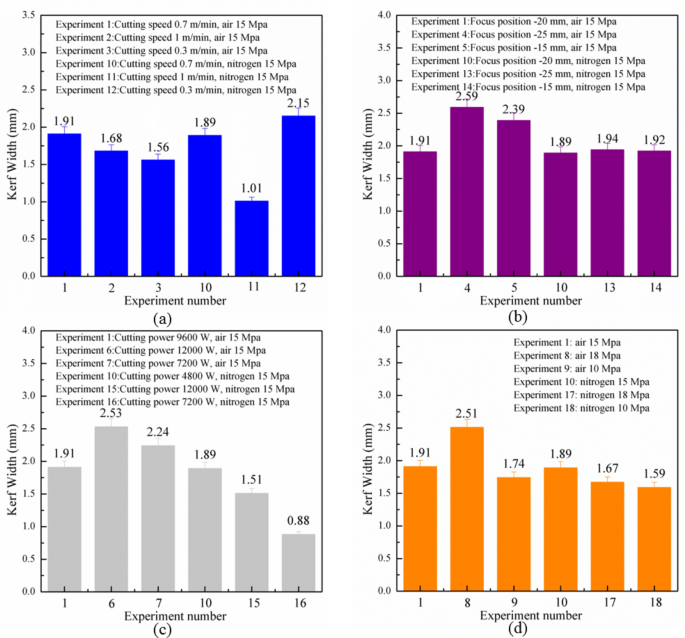

Surface roughness under different cutting parameters. (a) Roughness at different cutting speeds. (b) Roughness at different focal positions. (c) Roughness at different powers. (d) Roughness at different air pressures.

Figure 7 illustrates the surface roughness variations under different cutting parameters, including cutting speed, focal position, laser power, and gas pressure. These parameters directly influence the smoothness of the cut surfaces, and understanding their effects is key to optimizing laser cutting performance.

The results show that lower cutting speeds (e.g., 0.3 m/min) lead to higher surface roughness due to prolonged heat exposure, which causes excessive material melting and rougher edges. Slower speeds result in larger heat-affected zones and material deformation, leading to rougher surfaces. In contrast, higher speeds (e.g., 1 m/min) minimize heat accumulation, creating smoother cuts. However, if the speed is too high, it may lead to incomplete cuts or inconsistent surface quality due to insufficient energy input. Therefore, a moderate cutting speed strikes the best balance between minimizing roughness and ensuring clean cuts. The focal position significantly impacts surface roughness. A deeper focal position (e.g., − 25 mm) concentrates energy more effectively within the material, reducing surface roughness as the laser focuses precisely on the cut zone. Deeper focal positions also minimize the heat spread across the surface, resulting in cleaner cuts. Shallower focal positions (e.g., − 15 mm) disperse the laser energy over a broader area, increasing surface roughness due to uneven energy distribution and higher heat input near the surface. The results indicate that a focal position between − 20 mm and − 25 mm produces the smoothest surfaces. Laser power plays a critical role in determining surface quality. Higher power (e.g., 12000 W) increases surface roughness due to excessive melting, which creates a rougher cut surface as more material is vaporized or left unevenly cooled. Lower power (e.g., 7200 W) produces smoother cuts as less energy is absorbed, resulting in a smaller heat-affected zone and less material melting. However, too little power may lead to incomplete cuts or inconsistent quality. The optimal power range (7200 W to 9600 W) provides sufficient energy to make clean, smooth cuts while minimizing surface roughness. The gas pressure influences the removal of molten material and surface oxidation. Higher pressures (e.g., 18 MPa) are effective in removing molten material from the cut zone, which can reduce surface roughness by preventing slag buildup. However, excessive pressure can lead to turbulence, causing surface irregularities and increasing roughness. Lower pressures (e.g., 10 MPa) result in smoother surfaces, as the gas flow is more controlled and minimizes slag formation. Nitrogen, being an inert gas, further reduces oxidation and promotes smoother cuts compared to air, as evidenced by the experiments using nitrogen at various pressures.

The surface roughness observed in Fig. 7 is primarily influenced by the interaction between the laser and material. Slower speeds, shallow focal positions, and higher power levels increase surface roughness due to excessive heat input and material melting. In contrast, higher speeds, deeper focal positions, and moderate power settings improve surface quality by minimizing heat effects. The choice of assist gas and its pressure also significantly affects the surface finish, with nitrogen and controlled gas pressures producing the smoothest cuts. Optimizing these parameters is essential for achieving the best surface quality in laser cutting processes.

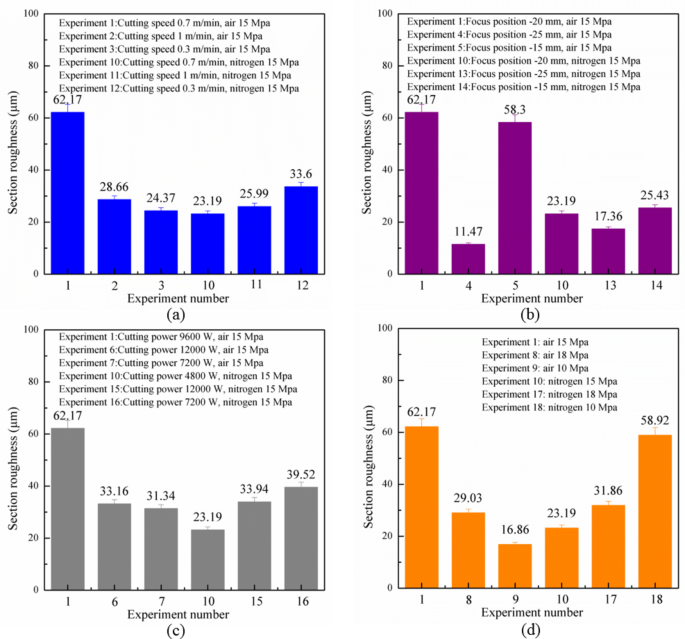

Enlarged views of the cross-section under different cutting conditions.

Figure 8 provides magnified cross-sectional images of fuel rods cut under different experimental conditions, revealing variations in cut quality, surface roughness, and slag deposition. These differences can be attributed to key laser cutting parameters such as cutting speed, focal position, laser power, and gas pressure. Below, we discuss the reasons behind these experimental phenomena and the observed data.

The influence of cutting speed is evident in the surface roughness and slag formation. Lower cutting speeds (e.g., Experiment 3) lead to excessive heat accumulation due to prolonged laser-material interaction. This results in greater material melting and significant slag deposition, as well as increased surface roughness. Conversely, higher cutting speeds (e.g., Experiment 2) reduce the interaction time, minimizing thermal effects and producing cleaner cuts with less slag. However, excessively high cutting speeds can compromise cut depth and quality, as the laser energy may not sufficiently penetrate the material. This trade-off highlights the importance of selecting an optimal speed that balances clean cuts with efficient material removal.

Focal position significantly impacts the concentration of laser energy on the material surface and depth. Deeper focal positions (e.g., Experiment 4, − 25 mm) concentrate the laser energy within the material, improving cutting precision and reducing kerf width. However, these deeper positions may also lead to excessive material melting and increased slag formation if not well-controlled. Shallower focal positions (e.g., Experiment 5, − 15 mm) disperse the energy more broadly across the surface, resulting in wider kerfs and more superficial cuts. The images in Fig. 8 show that a focal position in the range of -20 mm to -25 mm achieves the best balance, with narrower kerfs and minimal slag formation.

Laser power determines the intensity of the energy delivered to the material. Higher power levels (e.g., Experiment 6, 12,000 W) generate increased heat, enabling faster cutting but also leading to more pronounced slag deposition and rougher cut surfaces. This is because excessive power can cause over-melting of the material, especially when combined with slower speeds. On the other hand, lower power settings (e.g., Experiment 7, 7200 W) result in smoother cuts and less slag but may struggle to penetrate the material effectively, particularly in the presence of the wire wrapping. The data suggest that a moderate laser power between 7200 W and 9600 W offers the optimal balance, providing clean cuts with manageable slag levels.

The assist gas plays a crucial role in removing molten material during the cutting process and preventing oxidation. The images in Fig. 8 indicate that higher gas pressures (e.g., Experiment 8, 18 MPa) facilitate better slag removal but can sometimes lead to surface roughness due to turbulence or improper molten material ejection. Lower pressures (e.g., Experiment 9, 10 MPa) reduce the effectiveness of molten material removal, resulting in more slag buildup on the cut surface. Nitrogen, due to its inert nature, generally produces less oxidation compared to air, which is evident in experiments using nitrogen assist gas (e.g., Experiments 13 and 14). However, the benefits of nitrogen are more pronounced at moderate pressures, where slag removal and cut quality are both improved.

The presence of stainless steel wire wrapping adds complexity to the cutting process by influencing how the laser energy is distributed across the surface. The wire acts as a thermal sink, drawing heat away from the rod and potentially leading to uneven melting along the cut surface. This effect is most notable at lower laser powers or when the focal position is not optimized. In the optimized settings (e.g., focal position of -20 mm to -25 mm, cutting speed of 1 m/min, and power between 7200 W and 9600 W), the wire does not significantly hinder the cutting process, and smooth, consistent cuts are achieved.

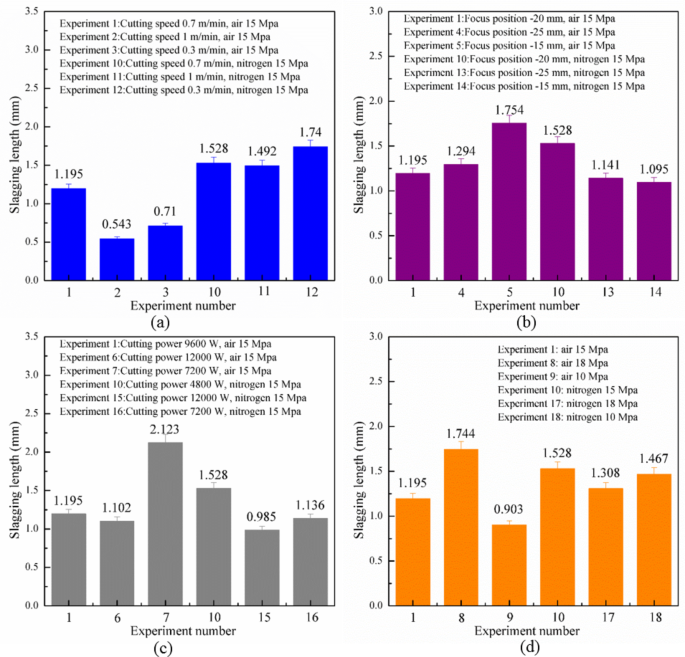

Length of spatter under different cutting parameters. (a) Length of spatter at different cutting speeds. (b) Length of spatter at different focal positions. (c) Length of spatter at different powers. (d) Length of spatter at different air pressures.

Figure 9 shows the length of spatter under different cutting parameters, including cutting speed, focal position, laser power, and gas pressure. The spatter length directly reflects how effectively molten material is removed during cutting and is a key factor in determining cut quality.

The spatter length decreases as cutting speed increases. At lower speeds (e.g., 0.3 m/min), the prolonged interaction between the laser and the material causes excessive melting, leading to larger amounts of molten material being ejected, and thus, longer spatter lengths. Higher speeds (e.g., 1 m/min) reduce this interaction time, resulting in less material melting and shorter spatter lengths. However, if the cutting speed is too high, the laser may not deliver sufficient energy to fully cut through the material, potentially leading to incomplete cuts. The focal position influences spatter length by affecting where the laser energy is concentrated. A deeper focal position (e.g., -25 mm) concentrates energy within the material, reducing spatter as less material is melted on the surface. Shallower focal positions (e.g., − 15 mm) disperse the laser energy over a larger surface area, causing more material to melt and leading to longer spatter lengths. The results suggest that deeper focal positions help control spatter formation by focusing energy deeper within the cut. Higher laser power (e.g., 12000 W) leads to increased spatter length due to excessive material melting and vaporization. More molten material is generated, which results in larger amounts of spatter being ejected. Conversely, lower power (e.g., 7200 W) generates less heat, reducing material melting and, therefore, shortening the spatter length. A moderate power setting (e.g., 9600 W) provides a balance between cutting efficiency and minimizing spatter. Higher laser power (e.g., 12000 W) leads to increased spatter length due to excessive material melting and vaporization. More molten material is generated, which results in larger amounts of spatter being ejected. Conversely, lower power (e.g., 7200 W) generates less heat, reducing material melting and, therefore, shortening the spatter length. A moderate power setting (e.g., 9600 W) provides a balance between cutting efficiency and minimizing spatter.

The spatter length is influenced by the balance of laser parameters. Higher speeds, deeper focal positions, moderate power, and controlled gas pressures contribute to shorter spatter lengths, while lower speeds, shallow focal positions, and higher power increase spatter due to excessive material melting. Optimizing these parameters is crucial for minimizing spatter and achieving cleaner cuts.