Radiation safety is a cornerstone of nuclear safety, playing a vital role across domains such as nuclear engineering, space exploration, medical physics, and various industrial applications1. In nuclear facilities, shielding is essential not only because of particles-induced activation structural materials—which leads to the emission of penetrating photon radiation (mostly gamma radiation)—but also because of its direct implications for personnel safety and long-term occupational health2. The effectiveness of shielding design directly affects exposure risks and is thus a critical determinant of facility safety compliance. Furthermore, shielding designs significantly influences the economic efficiency and overall feasibility of facility construction3. As such, accurate modeling of photon interactions with matter is fundamental to optimizing protection while balancing cost and performance. Nonetheless, it is indispensable throughout the entire lifecycle of nuclear applications—including design, construction, commissioning, operation, and real-time monitoring—making it a core component of radiation safety and regulatory strategy4.

As such, accurate modeling of photon interactions with matter is fundamental to optimizing protection while balancing cost and performance. This work is therefore of direct interest to a wide range of specialists, including nuclear engineers designing shielding for reactors and waste storage, medical physicists ensuring nuclear and staff safety during radiological procedures, aerospace engineers protecting astronauts and equipment from cosmic radiation, and AI scientists developing data-driven models for design and analysis of complex nuclear system.

Traditionally, the most widely used approach for simulating radiation transport is based on solving the Boltzmann Transport Equation (BTE)5. This method divides space into discrete units and applies the law of conservation of particles to model the inward and outward flows of particles in each unit. The traditional BTE can be formulated as in Eq. 1, where ψ represents particles flux.

$$\Omega \cdot \nabla \Psi \left(r,\Omega ,E\right)+{\Sigma }^{{\rm{T}}}\left(r,E\right)\Psi \left({\rm{r}},\Omega ,{\rm{E}}\right)$$

$$={\int }_{0}^{\infty }d{E}^{{\prime} }{\int }_{4\pi }d{\Omega }^{{\prime} }{\Sigma }^{S}\left(r,{\Omega }^{{\prime} }\to \Omega ,{E}^{{\prime} }\to E\right)\Psi \left({\rm{r}},{\Omega }^{{\prime} },{{\rm{E}}}^{{\prime} }\right)+S\left(r,\Omega ,E\right)$$

(1)

However, solving the BTE is a tough task due to the equation’s dependence on particle flux variations over time t (for a transient problem), angle \(\Omega (\phi ,\theta )\), space D, energy E, and coordinates \(r(x,y,z)\), involving up to seven independent variables, making it computationally intensive6. The deterministic method, which discretizes the equation and divides it into several energy groups, requires the construction of a coefficient matrix. The solution to the resulting system of equations provides the multi-group particle flux. Despite its widespread use, this method requires space and angle homogenization7 and is time-consuming to apply in three-dimensional scenarios, rendering it unsuitable for rapid real-time analysis.

In contrast, the Monte Carlo (MC) method does not directly solve the BTE but leverages the law of large numbers as in Eq. 28,9, which draws distributions. In Eq. 2, Xi represents the final score from a single, complete particle history—for example, the contribution of the i-th particle to the flux in the detector. The simulation is run for n total particle histories. According to the Law of Large Numbers, by averaging the scores from a sufficiently large number of these independent particle histories, the calculated sample mean converges to the true physical quantity μ, which is the expected value of the particle flux.

$$\mathop{\mathrm{lim}}\limits_{n\to \infty }\frac{1}{n}\mathop{\sum }\limits_{i=1}^{n}{X}_{i}=E({X}_{i})=\mu $$

(2)

The method simulates many particle trajectories, considering all detailed physical interactions and continuous cross-sections calculation, making MC the most accurate method10,11,12. However, it requires simulating millions, or even billions, of particles, with a typical simulation involving at least 10 million particles. A major challenge arises in complex shielding scenarios, where particles may not reach points of interest, leading to low estimates and high variance in results. Advanced techniques, such as importance sampling13,14, weighted windows15, and the MAGIC method16, have been developed to mitigate these issues, but MC simulations can still require extensive computation times (often tens or hundreds of hours). As such, it is impractical for real-time simulations, such as rapid risk assessments that nuclear safety needs urgently.

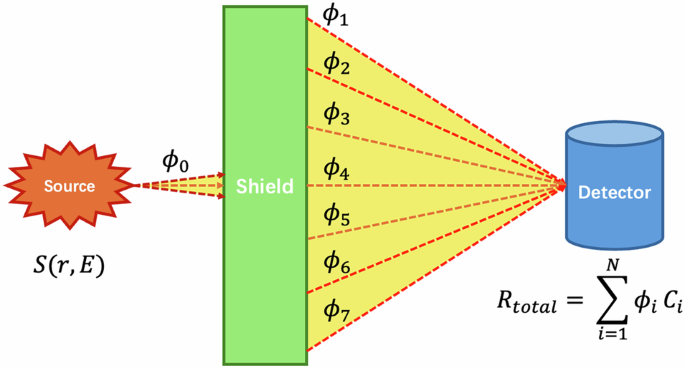

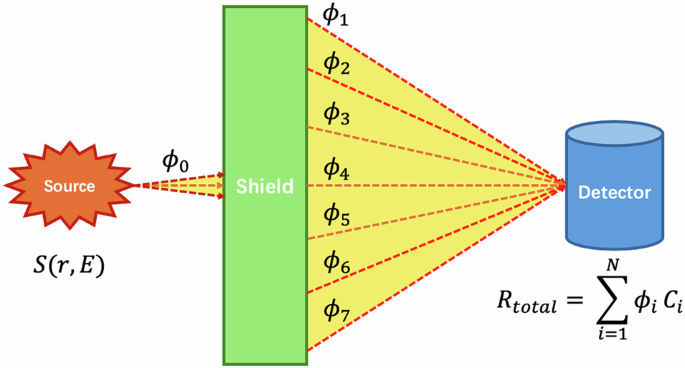

To bridge the gap between the high accuracy of conventional methods and the need for real-time shielding calculations, the Point Kernel (PK) method was introduced17. The PK method simplifies the BTE by reducing it to an attenuation law for photons, rendering the most suitable for nuclear practices. Assuming in total of n energy groups are considered; the PK formulation can be expressed as in Eqs. 3, 4. Figure 1 illustrates the relationship between source, scattered flux and responses in shielding analysis18,19.

$${\phi }_{r,k}=\frac{{I}_{0}({E}_{0})}{4\pi {r}^{2}}{e}^{-\mu r}{F}_{r,k}$$

(3)

$$R(r,{E}_{0})=\mathop{\sum }\limits_{k=0}^{n}{\phi }_{r,k}{C}_{k}=\mathop{\sum }\limits_{k=0}^{n}\frac{{I}_{0}({E}_{0})}{4\pi {r}^{2}}{e}^{-\mu r}{F}_{r,k}{C}_{k}=\frac{{I}_{0}({E}_{0})}{4\pi {r}^{2}}{e}^{-\mu r}B({E}_{0},r)$$

(4)

Shielding process with a photon radiation source. High-energy photon beams undergo complex physics process then reach the detector.

Fig. 1 illustrates the core concept of the shielding analysis. A source S(r, E) emits photons, resulting in an uncollided flux component \({\phi }_{0}\), that passes directly through the shield. Interactions within the shield also generate a scattered photon field, which is categorized into multiple energy groups (symbolized by \({\phi }_{1}\) through \({\phi }_{7}\)). The total detector response Rtotal is calculated by summing the contributions from all flux components (both uncollided and scattered), where the flux in each group ϕi is weighted by its respective energy-dependent conversion factor \({C}_{i}\).

In Eqs. 3, 4, the subscript k means the k-th energy group of scattered photons. In most cases, source information such as intensity \({I}_{0}\), energy \({E}_{0}\) is readily available, allowing the response at any point in coordinate r to be calculated. The equation divides photon contributions into two components: uncollided flux \(\frac{{I}_{0}({E}_{0})}{4\pi {r}^{2}}{e}^{-\mu r}\), which represents photons that have not interacted along their path (here μ represents linear attenuation coefficient), and scattered flux \({\phi }_{r,k}\), which represents photons that have undergone scattering20. Different from traditional Point Kernel formula, the term \({F}_{r,k}\) represents relative photon flux, which is defined as ratio of \({\phi }_{r,k}\) versus uncollided flux. The physical quantity of interest is modified by a coefficient \(B({E}_{0},r)\) called the buildup factor (BF), which represents the ratio of the total flux response \(R(r,{E}_{0})\) to that of the uncollided fluence21,22. Thus, the accuracy of the PK method depends directly on the accuracy of the BF.

Since the introduction of the PK method, extensive research has been conducted to refine the determination of BF. The most widely used BF dataset, based on the ANSI-6.4.3-1991 report, covers several common shielding materials and 22 elemental substances23. For missing elements, interpolation based on atomic number is used, and existing data is fitted using the Generalized Polynomial (GP) method.

However, the limitations of the ANSI dataset are multi-faceted and significant. Firstly, the ANSI/ANS-6.4.3 standard is critically outdated, with much of its underlying data based on calculations from decades prior that fail to incorporate substantial advancements in nuclear data, physics models, and computational power. Its official withdrawal by ANSI acknowledges its inadequacy for contemporary needs. Secondly, the buildup factors in the ANSI standard were derived using outdated techniques, such as the moment method, which inherently simplify transport physics. This simplification led to the neglect of important physical processes like coherent scattering and bremsstrahlung effects, which can result in a non-conservative underestimation of dose. Thirdly, the ANSI dataset’s scope is severely limited, predominantly providing data for only two dosimetry quantities: exposure and energy absorption buildup factors. This restricts its utility, as the data cannot be adapted for other necessary response functions. Fourthly, the material coverage of the ANSI standard is insufficient for modern applications, providing data for only 22 elemental substances.

The outdated nature of the ANSI dataset has spurred numerous efforts for updates. For instance, research from Tsinghua University24,25, as well as studies in the United States by Lawrence and others, have worked to expand the BF dataset, using the MCNP code and other techniques to calculate BF with more precise simulations26,27. Recent advancements in shielding material research have led to further efforts, such as the use of the Discrete Particle Method combined with Monte Carlo simulations to calculate BFs for materials like lead, tungsten28, and polymer composites29. However, most of these studies are limited to calculations of limited types of materials, within a small range of thickness. Recently, Sun from CAEP conducted Monte Carlo simulations on four commonly used materials with detailed physics models. Thicknesses of up to 100 mean free paths (MFPs) were evaluated, demonstrating that conventional ANSI data tend to underestimate results and further proving the necessity of updating buildup factor (BF) data30. Despite the recognized importance of photon shielding studies, prior research has fallen short of delivering comprehensive coverage across nuclides—primarily due to the prohibitive computational cost of Monte Carlo-based simulations. Even with variance reduction methods in place, the simulation of a single case can take hours, severely limiting scalability. Consequently, the field has long lacked a complete and accessible dataset.

Moreover, existing efforts to update radiation shielding datasets remain largely limited to specific response quantities, such as exposure dose or effective dose estimates. While useful, this level of simplification is increasingly inadequate in the context of rapidly advancing data-driven methodologies. In rapidly advancing fields such as artificial intelligence, researchers have explored the use of AI technologies to achieve faster and more comprehensive representations of original BFs31. However, existing efforts have primarily focused on fitting ANSI-style data, while suffering from insufficient amount and style of training data containing more physics information32,33.

At present, no comprehensive efforts have been made to construct datasets based directly on photon shielding flux spectra. With the rise of artificial intelligence in radiation analysis and design, there is a growing demand for more detailed and continuous field data, rather than single-value data. Such fine-grained spectral data are essential for enabling AI models to learn, generalize, and make accurate predictions across diverse shielding scenarios. Therefore, the structure of shielding datasets must be fundamentally updated—moving toward higher-resolution, spectrum-based representations—to support modern computational tools and improve the fidelity of shielding analysis.

Recognizing the multi-faceted limitations of previous datasets, this work introduces the Photon Shielding Spectra Dataset (PSSD) to provide a modern, comprehensive, and physically robust solution. To resolve the insufficient material coverage and limited scope of the ANSI standard, the PSSD provides full, relative photon flux spectra for the first 92 elements of the periodic table. This spectral format offers superior flexibility, allowing the calculation of diverse dosimetry quantities, while the expanded material coverage meets the needs of modern applications. To correct the outdated and methodologically flawed foundation of previous data, this dataset was generated using the high-fidelity Reactor Monte Carlo (RMC) code, which incorporates detailed photon physics models. The extensive simulations, spanning 22 incident energy points and thicknesses up to 40 MFPs, were conducted on a supercomputing platform, consuming nearly one million CPU core-hours to produce a comprehensive and reliable foundation for advanced nuclear safety analysis.

This work presents three major contributions: (1) It leverages the latest nuclear database and incorporates detailed photon physics models to calculate layered shielding energy spectra for various incident radiation sources. The dataset includes data for 92 nuclides, making it the most comprehensive dataset available for elemental nuclides; (2) The dataset facilitates calculations for a broad range of radiation dosimetry quantities. Unlike previous methods that focused solely on BFs for absorbed dose and exposure dose, the dataset offers superior flexibility and applicability across diverse engineering scenarios; and (3) By providing results as spectral fields rather than single-point values, this work enables a more detailed analysis of energy layers in shielding, offering a new reference for shielding design and calculation, and providing resources for further research integrated with advanced AI technology.