ITER will be the largest Tokamak ever constructed, and it will produce orders of magnitude more neutrons than its predecessor (up to 107 times more), JET1, and other current private initiatives2. According to French nuclear licensing procedures, ITER is classified as Installation Nuclear de Base INB-174 under French regulation. Ensuring that the expected radiation conditions do not pose challenges and risks to equipment and humans, has made nuclear analysis a relevant computational discipline in support of the ITER design and licensing during the last two decades. The radiation safety case of ITER, structured around the computational codes MCNP3 and D1SUNED4, receives growing attention as the construction progresses. Monte Carlo method accuracy and code robustness accumulated over decades of use are the basis for MCNP selection by ITER Organization, while D1SUNED is an extension to boost MCNP performance needed to deal with ITER nuclear analysis computational particularities. Independent examination has explicitly identified the need to provide additional robustness to the prediction of three-dimensional radiation fields5.

ITER presents particularities requiring adaptations and innovations in the discipline. Geometry representation in MCNP stands as one of the most relevant ones. Materials as different as steel, water, beryllium, copper and air are deployed in intricate cm-scale shapes over dozens of meters. Homogenization of materials can result in large distortions of the radiation field prediction, the sense and size of which cannot be anticipated, thus representing an undesired approach6. Thanks to the development of tools such as Spaceclaim (www.spaceclaim.com) for geometry handling and SuperMC7 for computer-aided design (CAD) geometry translation to MCNP format, an ever-growing degree of detail has been captured over the years in successive models.

However, this approach implied an increased workload to prepare simulation inputs. To save time and to standardize the modeling of the environment to any simulation, ITER Organization coordinated a strategy of making reference models available to any user. They are arranged in two families: the Tokamak models8,9,10 and the Tokamak Complex models11,12,13 (representing the nuclear buildings). Despite the increased computational demand, most of the analyses conducted for ITER have been successfully carried out using them. Nevertheless, due to the usability of the models and computational limitations, it was necessary to keep both families apart.

Considering separate reference models for the machine and the building entails raising concerns. Situations in which the source of radiation is represented in a different model than the region of interest cannot be characterized with one single simulation. The same applies to situations in which the sources and/or regions of interest transcend the boundary between reference models of both families. Topics of relevance for the ITER safety case are affected.

To date, different artifacts have been considered to deal with this limitation on a case-by-case basis. All of them present drawbacks regarding the practicality, accuracy, codes licensing policies, compatibility with the ITER-specific environment of nuclear analysis tools, and/or simplicity of the analysis. They represent obstacles for an agile design process and affect the robustness of the safety case5.

The development of a heterogeneous model of the complete ITER Tokamak10 advances in the computational performance of D1SUNED, and a set of tools in support of weight windows technique14,15 have brought the possibility of joining the reference model families in a single integral model of the ITER facility, including both the Tokamak and the Tokamak Complex: the ITER full model. We present the model and two illustrative applications of high relevance for the ITER design and the safety case assessment. Model usability and computational viability to provide clean evaluations while avoiding the use of any artifact is thus demonstrated.

This work represents the culmination of a two-decade-long effort of ITER modeling8,9,10,11,12,13, methods development11,16, and implementation of tools7,17,18 to predict the radiation conditions in the ITER facility. It involves the simplification of the safety-related analysis for the benefit of clarity and standardization of the approach and reduces both human and computational resource demands. In practical terms, it means abandoning artifacts for the benefit of improved robustness of the nuclear analysis.

ITER MCNP reference models

The reference models of the ITER Tokamak have been in use and constant improvement for over two decades following or even triggering methodological advances. The number of MCNP surfaces is a good indicator of the complexity of a model. Initial versions consisted of <2000 surfaces to represent a single 20° sector of the machine. The adoption of CAD-to-MCNP translation tools, prominently SuperMC7, the inclusion of SpaceClaim (www.spaceclaim.com) in the workflow, and the development of guidelines and standardized approaches represented steep advances and boosted international collaboration. A successful 40° model series was developed over 12 years for applications related to regular sectors of the machine: A-lite, B-lite, C-lite, and C-model8. A similar development took place for the 80° irregular sector of the machine9 (containing the Neutral Beam Injector). In 2020, the first 360° model of the ITER Tokamak was built: E-lite10. In parallel, diverse MCNP models of the ITER Tokamak Complex were created in 201011, 201612, and 202013. Details on the number of surfaces are given in Table 1.

The complexity captured in the Tokamak models increased by a factor of ~100 in ~12 years. A similar trend is observed for the Tokamak Complex models, involving rising computational loads in either case19. This was the motivation to keep the Tokamak and the Tokamak Complex reference models apart.

Use of the current reference models

Note the mentioned ITER reference models contain, by definition, a non-exhaustive representation of the facility. They include either sectors of the machine inside the bio-shield, or the Tokamak Complex beyond the bio-shield. The same logic applies to radiation source representations considered within these models and to the regions of interest that can be studied: their maximum spatial extent will be delimited by the boundaries of the models. This feature is referred to as a partial representation captured in the models. Working in such conditions is referred to as a local approach, and it becomes more valid as the range of the dominant interactions gets narrower.

A myriad of local studies used the partial reference models to successfully address specific design topics and have constituted the core of the discipline. Numerous aspects of the radiation field of ITER were identified and accurately characterized thanks to the complexity captured in the reference models. For example, the role of the particles streaming through the gaps in the shutdown dose rates20 (SDDR), SDDR cross-talks between adjacent ports21, the nuclear heating peak values in the Vacuum Vessel inner shell22, or integral heating in the Blanket Shield Modules6. Note, however, that all of them are conducted in a local approach since they consider models dismissing regions either from the geometry or the radiation source. This has been widely acceptable since a relative evaluation or a confined phenomenon was addressed, rather than an absolute judgment of long-range aspects of the radiation field. Note this approach is sufficient, and even efficient, under certain circumstances.

Local approach shows, however, limitations when the geometries, radiation sources and/or regions of relevance become wider and eventually transcend the model’s boundaries. This situation has manifested in the last years in a set of works, and diverse attempts to mitigate it have been set in place.

A group of works23,24,25,26,27 took the approach of locally expanding the ITER reference models (A-lite23,24, B-lite25,26 and C-model27) in terms of geometry to address nuclear analysis of the Torus Cryopump Port #12 port cell25,26, the equatorial port bio-shield plug23 or the Neutral Beam Injector Cell24 and a dedicated shielding cabinet for the Radial Neutron Camera27. This permitted to include radiation sources of relevance and tallies over regions of interest. To some extent, this approach can be understood as increasing the study domain by extending the models. This is, building ad hoc dedicated larger-but-still-partial models. While it serves the purpose of facilitating a given study, the lack of generality of this approach is evident. Further, it remains difficult to quantify the impact of this approach.

Differently, other works explored the possibility of sewing simulations using different models to build a wider domain of study by concatenating studies in subsequent domains. This is made by transferring radiation transport information from one simulation to the next one. The radiation impinging on the boundary of a model needs to be characterized and reconstructed in the next one. The simplest procedure is the setting of a tally, inspecting it, and inferring an SDEF card (the standard approach for sources definition in MCNP) from it, which was made in some cases to study the upper launchers28, the upper port #1829 and a bio-shield plug generic design30. Note, however, that the SDEF cards are limited to one-level variable dependencies, which prevents proper modeling of the dominating effect of radiation streaming (focused, locally intense and highly energetic radiation beams). Furthermore, this approach is accompanied by an avoidable field distortion due to binning unapproachable to the date. Methods for uncertainty propagation associated with this approach are largely missing.

More generally, the use of WSSA files (i.e. binary surface source writing file), recording weight, coordinates, velocity vectors, and energy of impinging histories, permits to carrying out of such an operation, capturing the full complexity of the radiation field in the model’s boundary, as it was considered in to study the equatorial port #1131 and the In-vessel Viewing System32,33. Its main drawback is, however, the cap in the sampling of source particles. The number of particles registered in the initial simulation is the maximum number of particles that can be simulated in the subsequent one. This can entail convergence problems. In addition, it may involve the manipulation of source description files occupying GBs, sometimes impractical.

Lastly, the limitations of the use of WSSA files were addressed with a dedicated tool, named SRC-UNED34. It automatically infers probability distribution functions in user-defined bins from WSSA files, which permits unlimited sampling with lighter files (~MB). On the other hand, in comparison with the SDEF card approach, it permits higher-level variable dependencies, while the field distortion due to binning remains. Note that SRC-UNED is an artifact embedded within an already complex workflow, requiring a documented verification and validation (V&V) plus a case-by-case binning validation. SRC-UNED has been used in works such as the shielding design to protect electronics35, the design of lower ports bio-shield plugs36, the assessment of the radiation conditions during in-vessel components extraction13, the bio-shield lid design37 and the production of radiation atlases16.

Thus, attempts to overcome the partial nature of the local studies derived from the use of the current ITER reference models exist, reaching what can be considered pseudo-integral representations. With different degrees of success, none of them is fully satisfactory, bringing different problems such as the proliferation of new models, lack of generality, or unassessed distortions in the radiation field. The underlying problem to all of them is the constant avoidance of an obvious situation: the integral representation of the facility requires models including everything.

ITER safety case and the need for an integral representation

Differently, to design tasks, a local approach based on partial representations results unsatisfactory for the safety case assessment. Most of the safety-relevant responses must be determined all through the facility and considering all relevant sources of radiation, with the aim of reaching a global and absolute perspective. It will demonstrate compliance with the limits for radiation exposure to the public, workers and electronics, as well as the minimization of the occupational radiation exposure (ORE) known as the As Low As Reasonably Achievable (ALARA) strategy. This will involve a collection of studies considering a few radiation sources and large regions of the facility.

The safety case will deal with several neutron and photon sources spread all across the entire facility (shown in Figs. 1 and 2): (1) plasmas of different species, (2) Deuterium—Deuterium (DD) and Deuterium–Tritium (DT) reactions in the Neutral Beam Injector components38, (3) high-energy particles following runaway electrons events, (4) activated structures and components39, (5) activated corrosion products across the Tokamak cooling water system (TCWS)40, (6) activation of water in the TCWS41 (16N and 17N, photon and neutron emitters), and (7) activated Tokamak dust impregnating components42.

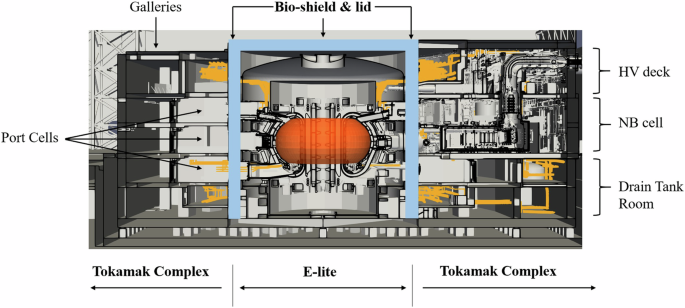

The plasma neutron source and the Tokamak Cooling Water System 16N photon source geometrical arrays are shown both in orange in the context of the ITER facility. The bio-shield and Lid are highlighted in blue. Note that the HV deck stands for a high-voltage deck, and the NB cell stands for a neutral beam cell. Courtesy of ITER Organization.

The bio-shield is highlighted in a white dashed line. Note that NBI stands for Neutral Beam Injector.

Timewise, instances of these radiation sources may dominate the radiation field during the pre-fusion power operation, during the fusion power operation phase, during machine shutdown and maintenance, as well as during the decommissioning. Space-wise, the full Tokamak pit, over 600 rooms in the Tokamak complex, which includes over 4500 penetrations in the walls, as well as the full extension of the ITER site up to the fence, are subject to study.

Facing the ITER safety case as a collection of local studies is unsatisfactory in terms of robustness, simplicity, and clarity5. Composing a global view as a patching of hundreds of local studies results is impractical. As explained, it requires artifacts introducing unassessed uncertainties and resulting more cumbersome as the study domain becomes wider or global for a simple reason: representing a single facility with two mutually exclusive models to determine the long-range situation is artificial from a methodological perspective. There is a growing perspective that an integral representation in a unified model might offer a more streamlined process for safety demonstration.