Alpha particle detectors are crucial for the operation and decommissioning of nuclear power plants. In these environments they are exposed to large doses of high energy alphas, neutrons and other forms of radiation1. Robust, high resolution, high sensitivity and low background detectors are an absolute necessity.

Diamond solid-state detectors are excellent alternatives to conventional scintillation and gas filled detectors. Diamond’s wide band-gap and large carrier mobility results in reduced leakage currents, fast signal collection2 and its radiation tolerance is unmatched by other semiconductors3. Furthermore, its low atomic number leads to a low capture cross section for gamma radiation, which reduces background noise caused by gamma-decay of activated materials or secondary decay of alpha particles. Diamond detectors have been used for alpha spectroscopy as far back as the 1970s4. Early diamond detectors utilised polycrystalline (PC) CVD diamond, leading to low charge collection efficiencies (CCE) due to charge trapping at grain boundaries and non uniform electric fields. The most success was achieved with carefully selected natural diamond, permitting CCEs of 100%5.

In recent years, techniques for growing commercially viable free-standing single-crystal (SC) diamond emerged and ‘electronic grade’ (ppb N) diamond in sizes up to 30 mm in diameter, are available. This has enabled the production of commercially available diamond radiation detectors (CIVIDEC). With numerous works demonstrating full charge collection, high resolution and fast response times (as low as 260 ps reported in6) for both alpha2,7,8 and neutron detection9,10,11,12,13,14.

The most common detector type is the MIM (Metal Insulator Metal) detector, which consists of an intrinsic diamond substrate sandwiched between two electrodes15. Alpha particles enter the detector through the top electrode and interact with the diamond, generating electron hole pairs (EHPs). A DC bias is applied across the detector and the EHPs move in the direction of the applied electric field, producing current. In order to achieve full charge collection, these detectors usually require large operating bias’ and careful selection of high quality SC diamond substrates. Additionally, alpha particles have a short penetration depth in all materials. For this reason MIM detectors are not desirable, as there is considerable energy absorption even in a thin metal top contact, which does not result in EHP generation, and therefore reduces CCE and resolution. Thus, planar detectors tend to be preferable. These consist of both electrodes on the alpha-facing surface, with EHP’s being separated transverse to the depth of the detector region and the radiation direction.

Furthermore, future high energy physics experiments and fusion reactors demand greater radiation fluences and \({>10^{16}}\) particles \(\mathrm {cm^{-2}}\)16,17 are expected. The RD42 collaboration conducted a study to measure the radiation tolerance of CVD diamond against protons, ions and neutrons of various energies16,18,19, and showed that at fluences of \(\mathrm {10^{17}\,cm^{-2}}\) the mean drift path of electron hole pairs reduced to 16 μm and the detector becomes trap limited, reducing the effective charge collection distance.

Thus innovative design approaches are needed to reduce the detector electrode spacing, L. One approach involves etching the diamond substrate to achieve an extremely thin membrane. Detectors as thin as μm have been achieved7, with close to 100% CCE. However thin membranes present challenges with regards to packaging the detector for use in harsh environments.

Here, an alternative approach is presented, involving fabricating a planar detector with internal electrodes, achieved using a pulsed laser, where the detector thickness is defined by the distance between internal electrodes rather than the substrate thickness. Diamond detectors for charged particle detection20,21, tracking22,23,24 and x-ray imaging25, have already been demonstrated using this approach. However, initial works were limited by the laser fabrication process, since it is difficult to fabricate the internal electrodes in close proximity to each other and the surface. This led to the need for large L and also limits the available geometries.

More recently an improved fabrication technique has been developed by the authors, which utilises a fs laser and adaptive optic elements to correct for aberrations in the diamond lattice. This method has enabled the production of conductive tracks with low resistivity and complex geometries26. These tracks have been termed Nano-carbon Networks (NCNs) due to the presence of various carbon forms, confirmed using high-resolution transmission electron microscopy27. Using this technology, detectors with close to 100% CCE have been demonstrated for particle tracking and X-ray imaging22,23,25 purposes. Furthermore, their durability in \(\mathrm {3.5 \times 10^{15} \, p \, cm^{-2}}\), has also been demonstrated18. However less attention has been paid to their use for alpha detection purposes.

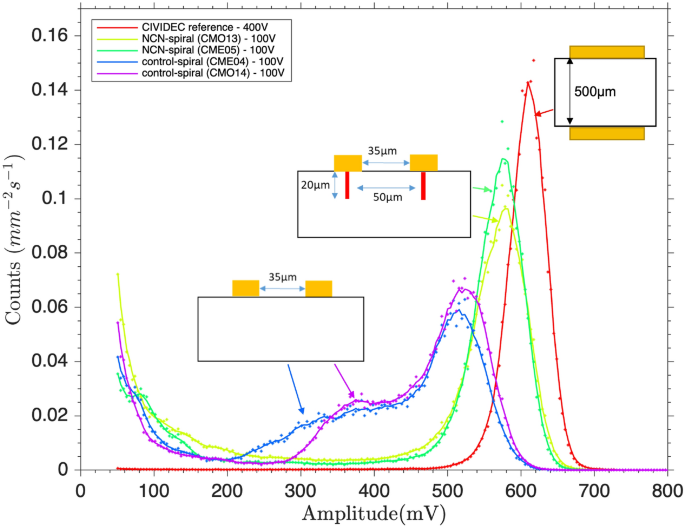

In this work planar configured detectors were fabricated, comprising two Ti/Pt/Au spiral electrodes separated by 35 μm on the alpha-facing surface of the diamond substrate. Similar structures, often referred to as planar detectors, have been adopted in numerous works22,23,28,29 but tend to demonstrate lower CCE when compared to MIM, membrane or three-dimensional detector architectures due to non uniform field distributions. Therefore three-dimensional internal NCN wall electrodes, following the same spiral pattern, chosen to optimise the uniformity of the electric field, were also fabricated underneath the Ti/Pt/Au surface contacts.

The fabrication of the NCN electrodes was as follows. First, a two-dimensional spiral NCN wire was fabricated, using a pulsed fs laser. The write process starts 20 μm below the surface, and builds up layer by layer to produce a wall height of 20 μm, reaching the top surface. This depth was chosen to correspond with the penetration depth of the test alpha particles. It is possible to increase the wall depth when designing a detector for other types of more penetrating radiation. Futhermore, it is envisioned that in the future the internal NCN electrodes could be contacted via the back of the substrate using NCN through vias, permitting removal of metal contacts from the alpha-facing surface, a known point of failure for detectors exposed to large doses of gamma radiation30.

The fabricated detectors were characterised. Firstly with Current-Voltage measurements and Raman spectroscopy. Secondly with alpha spectroscopy and transient current measurements during exposure to alpha particles from a sealed 241Am (Americium-241) source.

They have also been compared to a reference MIM detector, the CIVIDEC B3 Spectroscopic detector (500 μm thick, operating at 400 V). To confirm the quality of this detector, transient current measurements were performed during exposure to 241Am alpha particles and the corresponding data is shown in S4. The mobility and saturation velocities were extracted and found to be typical of high quality diamond substrates operated at high field8,31.