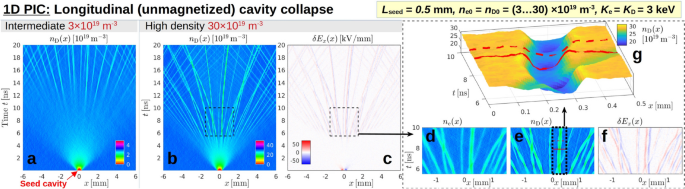

Longitudinal dynamics (1D, unmagnetized): excitation of solitary micro-cavity waves (Fig. 4)

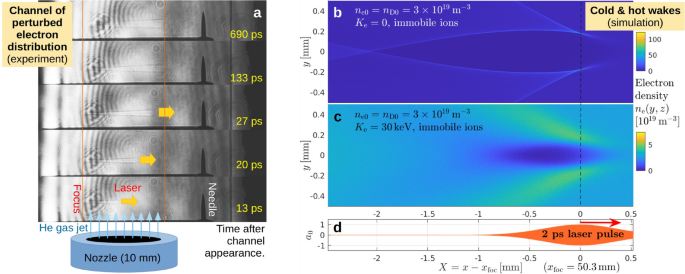

A sufficiently violent collapse of the cavity in the unmagnetized (x) direction may trigger the formation of solitary structures that, albeit microscopic, could be long-lived and arise in large numbers. This is demonstrated in Fig. 4, where we present results of 1D PIC simulations of such a collapse, starting from a small vacuum cavity. Recall from Fig. 3 that the laser-induced vacuum cavity can easily have a length L on the order of \(100\,\textrm{mm}\) or more. In the present case, however, we use only a very short seed cavity with \(L_{\textrm{seed}} = 0.5\,\textrm{mm}\). The primary motivation for this choice is the need to minimize boundary effects by providing a sufficiently large reservoir of thermal electrons on both sides of the cavity. Here, we choose a box size of \(L_x = 12\,\textrm{mm} \gg L_{\textrm{seed}}\) with periodic boundaries, so that the ambient density would drop by at most \(4\%\) if the \(0.5\,\textrm{mm}\) wide cavity was filled completely. We assume that the ions in the laser wake channel already underwent a Coulomb explosion, so we simply removed all electrons and ions from the cavity at \(t=0\). Thus, the initial phase of this simulation consists of the impingement of \(3\,\textrm{keV}\) Maxwellian deuterons, which wipe out the ion cavity within a nanosecond as can be seen in Fig. 4a,b. The electrons follow suit within \(\pm \lambda _{\textrm{D}}\). The absence of a magnetic field and the small initial size of the cavity means that this 1D setup may also be taken as a proxy for the case where a laser had been shot transversely (or at a steep angle) with respect to an ambient magnetic field.

EPOCH simulation of the thermal collapse of a 1D cavity surrounded by a \(3\,\textrm{keV}\) deuterium plasma with intermediate (a) and high density (b)–(g). The initial state is a \(12\,\textrm{mm}\) long neutral plasma with periodic boundaries. A seed cavity of length \(L_{\textrm{seed}} = 0.5\,\textrm{mm}\) with sharp boundaries is located around \(x=0\). This simplified setup is meant to represent a laser-induced vacuum cavity (after a Coulomb explosion) and to capture aspects of the plasma dynamics along an ambient magnetic field. The colored contour plots in panels (a) and (b) show the evolution of the deuteron density profile \(n_{\textrm{D}}(x)\) for \(n_0 = 3\times 10^{19}\,\textrm{m}^{-3}\) and \(30\times 10^{19}\,\textrm{m}^{-3},\) respectively. For the high-density case, panel (c) shows the electric perturbation \(\delta E_x(x)\). The data in the dashed rectangles are enlarged in panels (d)–(f), including also a plot of the electron density \(n_{\textrm{e}}(x)\). The density landscape of a solitary cavity from panel (e) is shown in more detail in panel (g), with solid and dashed red lines drawn for orientation at \(t = 7.9\,\textrm{ns}\) and \(8.7\,\textrm{ns}\), where the cavity has contracted and expanded, respectively. See Supplementary Fig. 7 for additional parameter scans.

Shortly after the initial collapse, Fig. 4a shows how the cavity spreads with a speed of about \(0.8\,\textrm{mm}/\textrm{ns}\) (\(\gtrsim v_{\textrm{th,D}} \approx 0.5\,\mathrm{mm/ns}\)) while it is being flooded with particles. At first, the particle distribution appears diffuse. However, after a few nanoseconds, a few dozen solitary structures become visible, which proceed to fan out from \(x=0\). In the high-density case in Fig. 4b, the diffuse phase looks shorter. Moreover, the solitary structures appear to interact more strongly, to the point that some of them oscillate around one another in bundles. Such mutual interactions (which are known to occur between multi-dimensional electromagnetic solitons25) are one important aspect that distinguishes the present 1D structures from ideal solitons, so we consider them to be solitary waves in a broader sense, meaning: long-lived nonnormal modes, whose structure is determined by a localized self-sustaining strong perturbation of the medium.

A detailed view of the structures and crossings of micro-cavities can be gleaned from panels (d)–(g) in Fig. 4. The boundaries of these solitary cavity waves appear sharper in the ion density (e) than in the electron density (d). Their apparent sizes vary and tend to be around \(\ell \sim 0.1\,\textrm{mm}\) in the present cases. Although the length scales are comparable, we do not see any obvious correlation with the Debye length, whose values are \(\lambda _{\textrm{D}} \approx 0.05\,\textrm{mm}\) and \(0.02\,\textrm{mm}\) in the two cases shown in Fig. 4. The electric perturbation \(\delta E_x\) in Fig. 4c,f is always positive on the left-, and negative on the right-hand side, both during the initial collapse of the seed cavity and in the solitary stage. This implies that, throughout the simulation, the cavity boundary consists of a double layer (sheath) with more electrons inside the cavity and more ions on the outside. This makes sense because, in the absence of an ambient magnetic field, there is nothing aside from electric forces to constrain the electrons’ streaming into the cavity with their high velocities, \(v_{\textrm{th,e}} \gg v_{\textrm{th,D}}\). The electric potential difference at each double layer in the solitary stage is about \(\ell |\delta E_x| \sim 2\,\textrm{kV}\), which is comparable to the thermal energy \(3\,\textrm{keV}\) of the particles in this simulation.

The particle density inside these solitary structures is about \(15 \cdots 20\%\) and \(25 \cdots 30\%\) below the respective ambient densities \(n_0 = 3\times 10^{19}\,\textrm{m}^{-3}\) and \(30\times 10^{19}\,\textrm{m}^{-3}\). While robust on long time scales of at least tens of nanoseconds, these solitary cavities can exhibit pulsations, which are perhaps visible most clearly in the surface plot in Fig. 4g. The density inside a solitary cavity wave decreases upon contraction and increases upon expansion, which seems to imply that the pulsations are due to a repeated flattening and steepening of its wall, during which particles flow all the way across the micro-cavity. The pulsation period seems to be about \(3 \cdots 4\,\textrm{ns}\) and \(1.5 \cdots 2\,\textrm{ns}\) for \(n_0 = 3\times 10^{19}\,\textrm{m}^{-3}\) and \(30\times 10^{19}\,\textrm{m}^{-3}\), respectively. Results of additional parameter scans can be found in Supplementary Fig. 7, where it is shown that a longer seed cavity tends to produce larger solitary cavities, and that the number, depth and interaction strength of the solitary structures varies with the temperature ratio, \(K_{\textrm{e}}/K_{\textrm{D}}\). A better understanding of the physics and relevance of these observations remains to be established through further study in 3D.

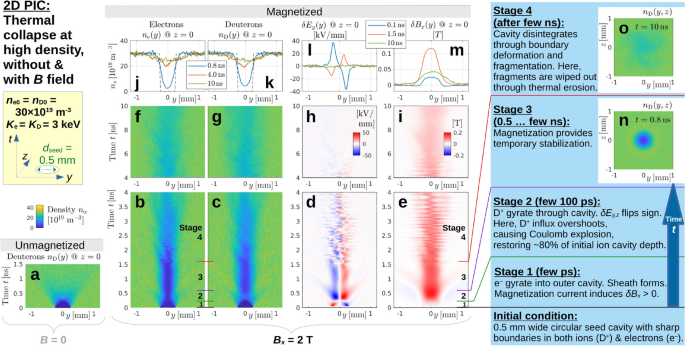

Transverse dynamics (2D): effect of magnetization, thermal ion influx, and cavity boundary instabilities

Figure 5 shows a summary of the main results of our 2D PIC simulations for the dynamics in the (y, z) plane transverse to the cavity axis x. Panel (a) shows that, in the absence of an ambient magnetic field (\(B = 0\)), our circular seed cavity is wiped out by the influx of thermal particles within a few \(100\,\textrm{ps}\) (as in the 1D case in Fig. 4). This illustrates the effect of high plasma temperature, which seems to have been negligible in the experiments shown in Fig. 1a. The result suggests that the plasma heating exerted by the prepulse in those laser experiments did not reach the keV-level energies that we are dealing with in the present simulations. Panels (b) and (c) of Fig. 5 show that our axial magnetic field \(B_x = 2\,\textrm{T}\) significantly prolongs the cavity’s life time by almost an order of magnitude. We distinguish four stages whose main features are outlined on the right-hand side of Fig. 5 and will be discussed in the following subsections. Different densities and field strengths will also be considered.

2D REMP simulation of the thermal collapse of a circular seed cavity with diameter \(d_{\textrm{seed}} = 0.5\,\textrm{mm}\) in the (y, z) plane surrounded by a \(3\,\textrm{keV}\) hot deuterium plasma, (a) without and (b)–(o) with an ambient magnetic field \(B_x = 2\,\textrm{T}\). Panels (a)–(c) show the temporal evolution of the density profiles \(n_\alpha (y)\) at \(z = 0\) of deuterons (\(\alpha =\textrm{D}\)) and electrons (\(\alpha =\textrm{e}\)) during the first few nanoseconds in the form of colored contour plots. Panels (d) and (e) show the evolution of the electromagnetic perturbations \(\delta E_y(y)\) and \(\delta B_x(y)\). Only a small portion of the \(12\,\textrm{mm}\times 12\,\textrm{mm}\) wide simulation box is shown. Time t advances upward and panels (f)–(i) show the continuation of the dynamics during the \(4 \cdots 10\,\textrm{ns}\) interval. Panels (j)–(m) show the y-profiles in more detail for a few snapshot times, with initial (\(t = 0\)) density profiles drawn as black dashed lines. We distinguish four stages, labeled 1–4, that are described on the right-hand side of the figure and in more detail in the text. Their transitions are roughly indicated by colored lines in panels (b), (c) and (e). Panels (n) and (o) show \(n_{\textrm{D}}(y,z)\) snapshots taken during stages 3 and 4. Here we used a fairly high density of \(30\times 10^{19}\,\textrm{m}^{-3}\). Results of a density scan are presented in Fig. 7.

Stages of a cavity’s thermal collapse at high density in 2D (Fig. 5)

The simulation shown in Fig. 5 was initialized with a \(d_{\textrm{seed}} = 0.5\,\textrm{mm}\) wide circular seed cavity that has a sharp boundary, where the density jumps abruptly from zero to its ambient value. A fairly high density of \(n_{\textrm{e0}} = n_{\textrm{D0}} = 30\times 10^{19}\,\textrm{m}^{-3}\)—as may be found in the central core of a tokamak—is used for both electrons (\(\textrm{e}^-\)) and ions. Here, the ions are deuterons (\(\textrm{D}^+\)).

The ambient Maxwellian plasma has a temperature of \(K_{\textrm{e}} = K_{\textrm{D}} = 3\,\textrm{keV}\), so that the electrons travel at a thermal speed of about \(v_{\textrm{th,e}} \approx 33\,\mathrm{mm/ns}\) and gyrate into the outer cavity within a few picoseconds. The resulting double layer (sheath) has a characteristic width comparable to the thermal gyroradius, \(\rho _{\textrm{Be}} \approx 0.1\,\textrm{mm}\). The charge separation may be difficult to see in the densities \(n_{\textrm{e}}(y)\) and \(n_{\textrm{D}}(y)\) plotted in Fig. 5b,c, but the associated electric field is clearly visible in Fig. 5d, where the electric perturbation \(\delta E_y(y)\) is shown. (In general, the sheath’s fine structure can be more complicated and multi-layered as we will see later in Fig. 6.) The associated \({\varvec{E}}\times {\varvec{B}}\) drift of the electrons is counter-clockwise in the (y, z) plane, which should produce a magnetic perturbation \(\delta B_x < 0\) that counters the ambient magnetic field \(B_x = 2\,\textrm{T}\) inside the cavity. However, Fig. 5e shows that the magnetic field inside the cavity is enhanced by a perturbation \(\delta B_x > 0\) with positive sign (appearing in red color), which must be due to the electrons’ magnetization current \({\varvec{j}}_{\textrm{mag}}\). All this belongs to stage 1, during which the ions still have hardly moved. The dominance of the magnetization current for magnetic induction persists throughout the simulation.

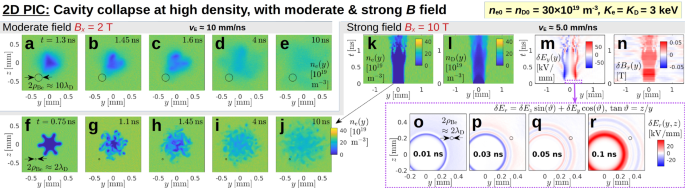

Comparison between the cavity evolution in a moderate and in a strong ambient magnetic field \(B_x\). Panels (a)–(e) show snapshots of the electron density field \(n_{\textrm{e}}(y,z)\) for \(B_x = 2\,\textrm{T}\) of Fig. 5b. Panels (f)–(j) show \(n_{\textrm{e}}(y,z)\) snapshots for the high-field case, \(B_x = 10\,\textrm{T}\), whose evolution can be seen in panels (k)–(r). A variant of this case and a density scan can be found in Supplementary Fig. 12.

The ions impinge onto the cavity with their thermal velocity \(v_{\textrm{th,D}} \approx 5.6\,\mathrm{mm/ns}\), which becomes noticeable within a few \(100\,\textrm{ps}\) for our sub-millimeter-sized cavity and is labeled as stage 2 in Fig. 5. Panel (c) of Fig. 5 shows that the ion cavity tends to collapse partially during the interval \(0.1\,\textrm{ns} \lesssim t \lesssim 0.5\,\textrm{ns}\), and the electrons in panel (b) follow suit to some extent, while being constrained by magnetization. One can see, by comparing panels (b) and (c) in Fig. 5 around \(t \approx 0.3\,\textrm{ns}\), that the ion influx exceeds that of the electrons. The resulting reversal of the electric field \(\delta E_y(y)\) is clearly visible in Fig. 5d. The associated \({\varvec{E}}\times {\varvec{B}}\) drift of the electrons also flips sign—now oriented clockwise in the (y, z) plane—and produces a magnetic perturbation \(\delta B_x > 0\) that adds to the enhancement of the ambient magnetic field \(B_x = 2\,\textrm{T}\) in Fig. 5e. Together with the field induced by the magnetization current, \(\delta B_x/B_x\) reaches about \(10\%\) (\(0.2\,\textrm{T}\)) in the present case.

The rapid formation (stage 1) and reversal (stage 2) of the electric field launches an electromagnetic (EM) pulse that can be seen in Fig. 5d,e during \(0.3\,\textrm{ns} \lesssim t \lesssim 1.5\,\textrm{ns}\) in the form of a perturbation that travels away from the cavity with a phase velocity of about \(v_{\textrm{EM}} \approx 1\,\mathrm{mm/ns}\), which corresponds to \(0.5\%\) of the speed of light c in vacuum. Its effective wavelength is about \(\lambda _{\textrm{EM}} \approx 2\,\textrm{mm}\), which corresponds to a frequency on the order of \(f_{\textrm{EM}} = v_{\textrm{EM}}/\lambda _{\textrm{EM}} \approx 0.5\,\textrm{GHz}\). It is interesting that the wave’s phase velocity happens to be close to the Alfvén speed of the ambient plasma, \(v_{\textrm{A}} = B_x/(\mu _0 n_{\textrm{D0}} m_{\textrm{D}})^{1/2} \approx 1.8\,\mathrm{mm/ns}\), which may facilitate resonant interactions with Alfvén waves or, rather, with their kinetic counterparts, since the wave number \(k_{\textrm{EM}} \equiv 2\pi /\lambda _{\textrm{EM}}\) is large in the sense that \(k_{\textrm{EM}}\rho _{\textrm{BD}} \sim 20 \gg 1\). The practical implications, if any, remain to be understood.

In the present case with relatively high density, the deuteron influx and the associated electric perturbation seem to overshoot. The ensuing Coulomb explosion restores about \(80\%\) of the initial ion cavity depth by the end of stage 2. This is followed by a relatively quiescent phase that may last a few nanoseconds and is referred to here as stage 3. The details of the force balance that underlies this quasi-steady state remain to be understood. We speculate that a key role is played by the electric field \({\varvec{E}}\), which diverts the ions around the cavity if \(|\delta E_y” \sim v_{\textrm{E}}/v_{\textrm{th,i}} \gg 1\), as we anticipated earlier in connection with Eq. (7). Indeed, we find that \(v_{\textrm{E}}(t = 1\,\textrm{ns}) \approx (20\,\mathrm{kV/mm}) / (2\,\textrm{T}) = 10\,\mathrm{mm/ns}\) is much faster than the thermal speed \(v_{\textrm{th,D}} \approx 0.5\,\mathrm{mm/ns}\) with which our gyrating \(3\,\textrm{keV}\) deuterons impinge on the cavity in this case.

Our approximately circular cavity—whose cross-section during the quasi-steady state is shown in Fig. 5n—is unstable to deformations, which become visible at about \(t \approx 1.5\,\textrm{ns}\) in the density profiles in Fig. 5b,c. We have not yet attempted to clarify the physical mechanisms that cause such instabilities, so our discussion of this matter in the following paragraphs will remain mostly limited to the phenomenological level. During stage 4, the cavity in Fig. 5 disintegrates and the fragments seem to disappear via thermal erosion during the course of a few nanoseconds. At \(t = 10\,\textrm{ns}\), which is the end of our simulation, panels (j), (k) and (o) of Fig. 5 show that very little remains of our cavity in the present high-density case.

In the following paragraphs, we discuss how the dynamics of our 2D cavity depend on the strength of the ambient magnetic field and the plasma density, based on the results shown in Figs. 6 and 7. The plasma temperature is kept at \(3\,\textrm{keV}\) in all cases.

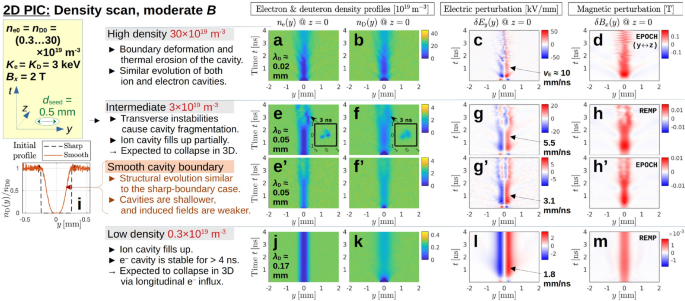

Results of 2D PIC simulations using EPOCH and REMP with densities in the range \((0.3 \cdots 30)\times 10^{19}\,\textrm{m}^{-3}\). As in Fig. 5, the color contour plots show the evolution of \(n_{\textrm{e}}(y)\), \(n_{\textrm{D}}(y)\), \(\delta E_y(y)\) and \(\delta B_x(y)\), arranged column-wise. For each case, the values of the Debye length \(\lambda _{\textrm{D}}\) from Eq. (5) and the \({\varvec{E}}\times {\varvec{B}}\) velocity \(v_{\textrm{E}}\) at \(t \approx 1\,\textrm{ns}\) are shown in columns (a) and (c), respectively. The high-density case (\(30\times 10^{19}\,\textrm{m}^{-3}\)) in panels (a)–(d) is essentially identical to that in Fig. 5b–n, demonstrating excellent agreement between the two codes in 2D. Here, a 3 times smaller box (\(4\,\textrm{mm}\times 4\,\textrm{mm}\)) was used since only the first \(4\,\textrm{ns}\) were simulated, during which thermal deuterons travel about \(2\,\textrm{mm}\). For the case with intermediate density (\(3\times 10^{19}\,\textrm{m}^{-3}\)), the results for the default (sharply bounded) seed cavity in (e)–(h) are complemented in (e’)–(h’) with results of simulations initialized with a smoothly bounded seed cavity (motivated by Fig. 2d). The initial density profiles with sharp and smooth cavity boundary are shown in panel (i) on the left-hand side. The main observations are described next to column (a) and in the text. More snapshots of the fragmentation process in the intermediate-density case (e)–(h) can be found in Supplementary Fig. 11, which also contains additional results for another initial condition. Notice that the low-density case (\(0.3\times 10^{19}\textrm{m}^{-3}\)) in panels (j)–(m) has \(\lambda _{\textrm{D}} \sim d_{\textrm{seed}}/2\), which permits significant charge separation on the cavity scale.

Cavity boundary instabilities and effect of a stronger magnetic field giving \(\rho _{\textrm{Be}} \ll d_{\textrm{seed}}\) (Fig. 6)

When the cavity collapses during stage 4 in Fig. 5, at the end of the quasi-steady phase, one can observe a deformation of the cavity boundary, followed by a fragmentation of the cavity itself. While the original symmetry breaking is presumably due to PIC noise and numerical inaccuracies, the instability develops in a relatively coherent fashion. The five snapshots in Fig. 6a–e show the form of this deformation in the electron density field \(n_{\textrm{e}}(y,z)\). First, the circular cavity acquires a triangular shape (a). Then it breaks up into a few fragments (b,c), which eventually disappear in a diffuse blur (d,e). The diffusion is expected to be a consequence of electron gyration, whose orbit is indicated as a black circle with diameter \(2\rho _{\textrm{Be}} \approx 0.2\,\textrm{mm}\) in Fig. 6a–e. Evidently, the gyroorbit’s size is similar to that of the seed cavity and its fragments.

Figure 6f–j shows how this instability is modified when the strength of the ambient magnetic field is increased by a factor 5 to \(B_x = 10\,\textrm{T}\), so that \(2\rho _{\textrm{Be}} \approx 0.04\,\textrm{mm} \approx 2\lambda _{\textrm{D}} \ll d_{\textrm{seed}}\). Instead of a triangular distortion, we now observe a boundary deformation in the form of a period-6 ripple that grows to a size comparable to the cavity radius as seen in panel (f). This structure then decays into many smaller fragments of scale \(\rho _{\textrm{Be}}\) in panel (g), which seems to lead to a turbulent state in (h)–(j).

The first \(1.5\,\textrm{ns}\) of the cavity’s evolution are shown in Fig. 6k–n. At first glance, the density cavities in (k) and (l) appear robust during the first few \(100\,\textrm{ps}\), but the electromagnetic perturbations in (m) and (n) reveal low-frequency (GHz) pulsations right from the start. It remains to be clarified whether the cavity boundary is linearly unstable to perturbations of arbitrary amplitude, or whether it is destabilized nonlinearly via an earlier overshoot of the electromagnetic fluctuations (or both).

The early sheath dynamics in the present case are more complicated than what we discussed in stage 1 of Fig. 5, where we had \(\rho _{\textrm{Be}} \approx 5\lambda _{\textrm{D}}\). In the present case, with \(\rho _{\textrm{Be}} \approx \lambda _{\textrm{D}}\), a multi-layered sheath develops that can be seen in Fig. 6o–q, which shows snapshots of the radial electric field \(\delta E_r = \delta E_z\sin \vartheta + \delta E_y\cos \vartheta\) with \(\vartheta = \arctan (z/y).\) However, within \(100\,\textrm{ps},\) the ion influx establishes again a positive \(\delta E_r > 0\) at the cavity boundary, as can be seen in Fig. 6r, whose polarization remains unchanged until the cavity collapses. Notice also that, as long as the original cavity remains intact, we have \(v_{\textrm{E}}/v_{\textrm{th,D}} \approx 5.0/0.5 = 10 \gg 1\), which is consistent with our earlier assertion that ion impingement is hindered by electric kicks.

Plasma density scan from small (\(\lambda _{\textrm{D}} \ll d_{\textrm{seed}}/2\)) to large Debye length (\(\lambda _{\textrm{D}} \sim d_{\textrm{seed}}/2\)) (Fig. 7)

The results in Figs. 5 and 6 were obtained with a high density of \(30\times 10^{19}\,\textrm{m}^{-3}\), that may be found in the core of a tokamak plasma. Results of a density scan towards lower densities relevant for the tokamak edge are shown in Fig. 7. The ambient field strength of \(B_x = 2\,\textrm{T}\) is the same as before. For easier comparison, Fig. 7a–d shows again the results of the high-density case, but now simulated using EPOCH.11 The results are essentially identical to those of REMP24 in Fig. 5b–e. Note that the values of \(\lambda _{\textrm{De}}\) and \(v_{\textrm{E}}\) referred to in the following discussion can be found, respectively, in columns (a) and (c) of Fig. 7.

As we have discussed in the previous section, both the electron and ion cavities in the high density case (\(30\times 10^{19}\,\textrm{m}^{-3}\)) are temporarily restored after an early partial implosion, but they eventually collapse within a few nanoseconds through what appear to be transverse instabilities. At high density, \(n_{\textrm{e}}\) and \(n_{\textrm{D}}\) in Fig. 7a,b evolve in a similar fashion when viewed on the spatial scale of the seed cavity, because \(\lambda _{\textrm{D}} \ll d_{\textrm{seed}}/2\) prohibits significant charge separation on that scale. This situation changes when one proceeds to lower densities—namely, \(3\times 10^{19}\,\textrm{m}^{-3}\) in Fig. 7e–h, and \(0.3\times 10^{19}\,\textrm{m}^{-3}\) in Fig. 7j–m, which are of interest for the plasma edge — where the Debye length \(\lambda _{\textrm{D}}\) approaches the size of our seed cavity radius \(d_{\textrm{seed}}/2\). The consequence is that the electron cavity remains deep during the quasi-steady phase in panels (e) and (j), while an increasing number of gyrating ions passes through the cavity in panels (f) and (k).

The cavity in the high-density case undergoes triangular distortion and fragmentation within \(1.5\,\textrm{ns}\), as we saw in Fig. 6a–c. In contrast, the quasi-steady state in the intermediate case in Fig. 7e–h lasts about \(2\,\textrm{ns}\), and—as the insets in panels (e) and (f) show—the cavity here undergoes elliptic distortion and decays first into a pair of fragments, which then decay further. (See Supplementary Fig. 11 for details and additional results obtained with another initial condition.)

In order to test whether the sharp boundary of the seed cavity is a cause of the ensuing instability, we repeated the simulation for the intermediate density with a seed cavity that started with a smooth boundary density profile of the form \(\sin ^4(\pi r/d_{\textrm{seed}})\) for \(r^2 = y^2 + z^2 \le (d_{\textrm{seed}}/2)^2\). This is motivated by the observations in Fig. 2d. The smoothed profile we used is plotted as a solid curve in Fig. 7i and approximately resembles the shape of the cavity seen at about \(0.8\,\textrm{ns}\) in Fig. 5j. The results are shown in Fig. 7e’–h’, where one can see that the overall dynamics are similar to what we saw in panels (e)–(h), both in structure and duration. At least for the present parameters, we see neither a stabilizing nor a destabilizing effect of the initial cavity profile. The main difference is that the electromagnetic perturbations \(\delta E_y\) and \(\delta B_x\) are only about half as strong in the case with smooth cavity boundary. (We note that the noisy ripples in Fig. 7g’ are most likely aliasing artifacts, since that simulation used a 15 times lower snapshot sampling rate than in panel (g).)

Notice that the electromagnetic perturbations in Fig. 7g’,h’ still exhibit some overshoot around \(0.3\,\textrm{ns} \lesssim t \lesssim 1\,\textrm{ns},\) which supports our earlier speculations that overshoots may be a cause of the ensuing instability. In contrast, there is hardly any overshoot in panels (l) and (m), where the electromagnetic perturbations of the low-density case (\(0.3\times 10^{19}\,\textrm{m}^{-3}\)) are plotted. The ion cavity in panel (k) fails to recover from its initial collapse and remains shallow thereafter. This observation is consistent with the fact that \(\lambda _{\textrm{D}} \sim d_{\textrm{seed}}/2\) in the low-density case, which implies that significant charge separation across seed-cavity-scale distances is now possible. Moreover, the magnitude of \(\delta E_y\) in Fig. 7l implies that the velocity ratio \(v_{\textrm{E}}/v_{\textrm{th,D}} \sim 1.8\) is of order unity in the low-density case, which means that the magnitude of the electric field may not suffice to divert impinging thermal ions. This consistency with observations can be taken as evidence to support our earlier conjecture that the electric deflection of ions may play a role in preventing them from flooding the cavity in the high-density case, where we had \(v_{\textrm{E}}/v_{\textrm{th,D}} \sim 10\).

To summarize these results: the overshoot and subsequent Coulomb explosion seen in the high-density case is weaker in the intermediate case, and absent in the low-density case. Meanwhile, the electrons in Fig. 7j are held back by the magnetic field and their cavity remains deep and robust for the remainder of this 2D simulation. A spectral analysis shows that the transformed cavity is only subject to rapid oscillations at the upper hybrid frequency26 \(\omega _{\textrm{UH}} = (\omega _{\textrm{pe}}^2 + \omega _{\textrm{Be}}^2)^{1/2} \approx 2\pi \times 57.4\,\textrm{GHz}\) (see Supplementary Fig. 14(i,j)), but it otherwise appears stable in 2D for at least \(4\,\textrm{ns}\) and perhaps much longer.

Of course, in three dimensions—with a laser wake channel of finite length and a curved magnetic field—the positively charged cavity seen in Fig. 7j can be expected to fill up rapidly via longitudinal electron influx along \(B_x\). In our \(3\,\textrm{keV}\) example, the thermal electron speed is \(v_{\textrm{th,e}} \sim 33\,\textrm{mm}/\textrm{ns}\), so that a \(100\,\textrm{mm}\) long cavity can be expected to be neutralized within \(10\,\textrm{ns}\) via longitudinal thermal streaming, which will presumably be enhanced by the attractive positive charge inside the ion-filled cavity. The next question is then whether the cavity will disappear without a trace or whether it will spawn solitary micro-cavities as seen in Fig. 4. Addressing this question will require 3D simulations, whose realization may require some more ingenuity.